The Impact of Overactive Bladder on Health-Related Quality of Life, Sexual Life and Psychological Health in Korea

Article information

Abstract

Purpose

We aimed to estimate the prevalence of overactive bladder (OAB) in Korea, to assess the variation in prevalence by sex and age, and to measure the impact of OAB on quality of life.

Methods

A population-based, cross-sectional telephone survey was conducted between April and June 2010 with a questionnaire regarding the prevalence of OAB, demographics, and the impact of OAB on quality of life. A geographically stratified random sample of men and women aged ≥30 years was selected.

Results

The overall prevalence of OAB was 22.9% (male, 19%; female, 26.8%). Of a total of 458 participants with OAB, 37.6% and 19.9% reported moderate or severe impact on their daily life and sexual life (5.6% and 3.5%, respectively, in participants without OAB). Anxiety and depression were reported by 22.7% and 39.3% of participants with OAB, respectively (9.7% and 22.8%, respectively, in participants without OAB). Only 19.7% of participants with OAB had consulted a doctor for their voiding symptoms, but 50.7% of respondents with OAB were willing to visit a hospital for the management of their OAB symptoms.

Conclusions

This study confirmed that OAB symptoms are highly prevalent in Korea, and many sufferers appear to have actively sought medical help. OAB has severe effects on daily and sexual life as well as psychological health.

INTRODUCTION

Overactive bladder (OAB) is a common disabling condition that affects health-related quality of life [1]. Estimates of the prevalence and impact of OAB on quality of life vary widely, in part due to variation in the assessment of symptoms, the populations surveyed, the methods used to collect data, and the criteria used to define OAB. OAB is a subset of storage lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS) defined as 'urgency, with or without urge incontinence, usually with frequency and nocturia'.

Previous reports from the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition (EPIC) study estimated the overall prevalence of OAB in Europe and Canada to be 12.8% among women and 10.8% among men, whereas the overall prevalence of any LUTS was estimated to be 62.5% in men and 66.6% in women [2]. In the US-based study, Stewart et al. [3] estimated the prevalence of OAB to be 16.0% among men and 16.9% among women. The Korean EPIC study, which was conducted in 2006, showed the overall prevalence of OAB to be 12.2% (10.0% of men, 14.3% of women) [4].

The impact of OAB on quality of life has been reported in foreign countries, but no population-based prevalence surveys have been published reporting the impact of OAB symptoms on aspects of psychological and sexual life in Korea.

The objective of this study was to evaluate the nationwide prevalence of OAB and the impact of OAB on quality of life regarding role limitation, sexual life, and psychological aspects (anxiety and depression). We also to aimed to investigate the difference in quality of life between patients with and those without OAB, and to study whether OAB symptoms were properly treated.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Between April 2010 and June 2010, a geographically stratified random sample of men and women aged ≥30 years and representative of the general population of Korea was selected for a telephone interview. A random sample of phone numbers was acquired through the Post and Address Registry of Korea. A two-step sampling method was adopted, in which step 1 entailed sampling of households with a residence telephone number, and step 2 entailed sampling of a single person within the household. Those who reported currently being pregnant or having a urinary tract infection were excluded. The interview was conducted after obtaining verbal informed consent.

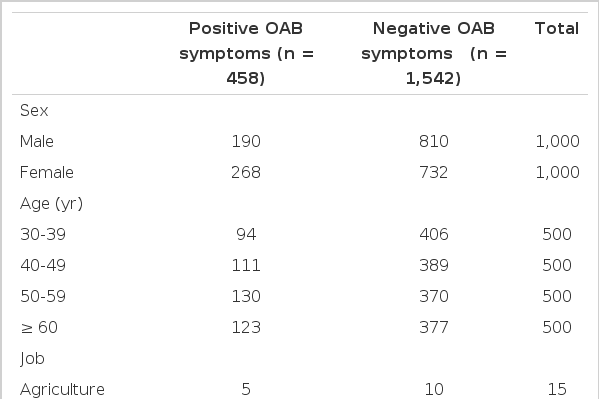

A questionnaire about OAB symptoms (overactive bladder symptom score, OABSS) was administered among subjects contacted by phone in whom a survey was feasible [5]. A total of 3 points with at least 2 points on question 3 was required for a diagnosis of OAB. Total scores of <5, 6-11, and >11 were considered mild, moderate, and severe, respectively. The basic demographic data collected consisted of gender, age, job, and education level (Table 1). Questions were asked to identify diseases that cause symptoms similar to OAB. Once OAB was determined on the basis of the OABSS questionnaire, whether a doctor had been consulted for OAB symptoms or treatment had been provided was evaluated. Also, the reason for no treatment and willingness to receive treatment were evaluated.

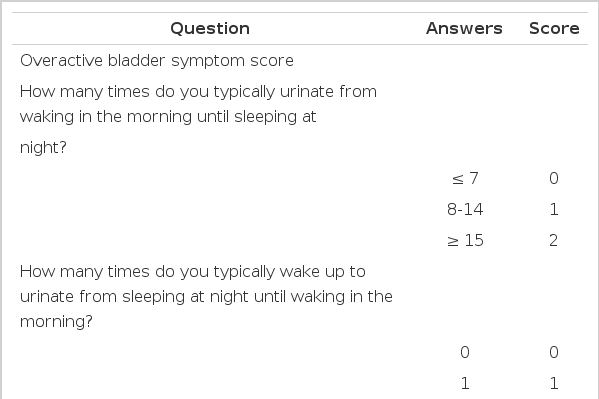

Two items modified from The Korean version of the King's Health Questionnaire (KHQ) were used to survey the impact of OAB on work, daily life, and sexual life, and the Korean version of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (K-HADS) was used to evaluate the impact of OAB on psychological aspects such as anxiety and depression. The KHQ was developed to evaluate the severity of OAB, bother, and quality of life, and it was used for OAB or urinary incontinence. The score of each item has 4 scales (Table 2). In this investigation, we evaluated the impact of OAB on quality of life by choosing 2 validated and modified items related to role limitations and personal relationships. Because the KHQ comprises only two simple questions to assess psychological effects such as anxiety and depression, the K-HADS was used for more in-depth analysis [6]. The HADS consists of a total of 14 questions designed to respond on a scale of 4 scores, and the K-HADS translated from the HADS has been standardized nationwide (Table 2). When the lower cut-off for depression was 8, the sensitivity and specificity of the HADS were shown to be 89.2% and 82.5%, respectively. When the lower cut-off for anxiety was 8, the sensitivity and specificity of the HADS were shown to be 78.8% and 82.5%, respectively. The construct validation was high in differentiating between abnormality and normality given the significant difference between the group with anxiety and depression and the normal group. The control group with no OAB symptoms was compared with subjects complaining of OAB symptoms.

Questions for the assessment of overactive bladder and the impact of overactive bladder on health-related quality of life

To analyze differences in prevalence by gender and age, subjects were stratified into age categories (30 to 39, 40 to 49, 50 to 59, and ≥60), and a total of 2,000 subjects with 250 men and 250 women in each age category were targeted for the survey. After a sample was drawn by simple random sampling, post-stratification was used. The percentages listed in the results are weighted. The crude prevalence of OAB was determined, and the data were analyzed by using stratification and a regression model to elucidate differences in symptom severity according to demographic data and a medical history. Differences in quality of life according to the presence or absence of OAB were compared by analyzing the above-mentioned questionnaires. Chi-square analyses were performed to test for significant differences between the proportions from categorical variables.

RESULTS

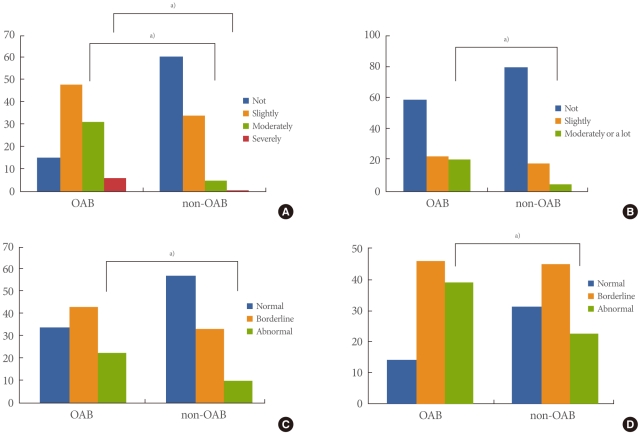

The overall prevalence of OAB was 22.9% (458/2,000), with prevalences of 19% among male and 26.8% among female Korean individuals aged ≥30 years. The prevalence of OAB was higher in women than in men at all ages, and the prevalence increased with age in men. In women, however, the prevalence was higher in the age group of 50 to 59 years than in the age group of ≥60 years (Fig. 1). More than 37% of participants with OAB reported moderate (31.4%) or severe (6.2%) bother of their daily life (housework, shopping, etc.) owing to OAB symptoms. By contrast, about 5% of participants without OAB reported moderate (5.0%) or severe (0.6%) bother (P<0.001; Fig. 2). Of 458 participants with OAB, 19.9% reported that OAB symptoms affected their sexual life. However, only 3.5% of participants without OAB reported that their sexual life was affected by OAB symptoms (P<0.001; Fig. 2).

Effects of overactive bladder (OAB) on daily life (A), sexual life (B), anxiety (C), and depression (D). a)P<0.001 by chi-square test.

The K-HADS was used to analyze the effects of OAB on anxiety and depression. Of 458 participants with OAB, 22.7% and 39.3% had anxiety and depression, respectively. In contrast, 9.7% and 22.8% of participants without OAB had anxiety and depression, respectively (P<0.001, P<0.001; Fig. 2). These results show that OAB affects psychological symptoms such as anxiety and depression.

Of all participants with OAB, 84.1% with OAB symptoms responded that it would be unsatisfactory if their voiding symptoms persisted for their lifetime. Only 19.7% of participants with OAB had consulted a doctor for their voiding symptoms, but 50.7% of respondents with OAB were willing to visit a hospital for the management of their OAB symptoms. In addition, 71.8% of participants with OAB responded that they would receive treatment if easy and successful treatment strategies for OAB were available.

DISCUSSION

OAB has traditionally been diagnosed on the basis of urodynamic investigation [7]. However, the application of such techniques is impractical in large epidemiologic studies of the general population. According to the current International Continence Society (ICS) definitions, OAB is a symptomatic condition characterized by urinary urgency with or without urgency incontinence, usually with increased daytime frequency and nocturia [8].

To date, a few large population-based surveys in Europe and North America have evaluated the prevalence of OAB. Two of these studies used an older definition of OAB [3,9]. Stewart et al. [3] estimated the US prevalence of OAB in adults aged ≥18 years to be 16% in men and 16.9% in women. In Europe, Milsom et al. [9] reported an OAB prevalence rate in adults aged ≥40 years of 15.6% for men and 17.4% for women. Note, however, that the older, broader definition of OAB comprised symptoms of frequency, urgency, and urge incontinence, occurring either singly or in combination. The EPIC study, which is the first large, population-based prevalence study using the 2002 ICS definitions, reported a prevalence of OAB of 11.8% (10.0% in men and 12.8% in women) [2]. The variety of definitions used to define bladder control problems, including OAB, has previously made it difficult to compare prevalence data across studies. For example, a meta-analysis of 48 epidemiologic studies of urinary incontinence found that prevalence rates vary considerably according to definition [10]. Despite these variations, those European and American studies consistently showed that the prevalence of OAB ranges from about 10 to 20%. By contrast, in Asian countries, the prevalence of OAB in women ≥18 years of age was reported to be 53.1% by use of a different definition of OAB, which was the presence of frequency, urgency, and urge incontinence, either singly or in combination [11]. Also, the prevalence in Asian men was 29.9% using the current ICS definition of OAB [12]. Those results may suggest that OAB symptoms are highly prevalent in Asia. However, in the recent Korean EPIC study, the prevalence of OAB was 12.2% (10.0% of men, 14.3% of women) [4]. Our study showed that 22.9% of the adult population in Korea aged ≥30 years has OAB. This difference may be due to the different age of the population and the definition of OAB used to make a diagnosis. In this study, the adult population aged ≥30 years was included. However, the Korean EPIC study included a younger population aged ≥18 years [4]. In consideration of the higher prevalence of OAB in older age groups, if a study includes a younger population, the overall prevalence of OAB may decrease. Our study used the OABSS to assess symptom bother and to diagnose OAB, whereas current ICS definitions were used for individual LUTS and OAB in the Korean EPIC study. The European study showed that the prevalence of OAB increased with advancing age and was equally apparent in both men and women [9]. Other studies performed in the United States and Korea reported that although the prevalence of OAB increased linearly in the male population, the prevalence decreased in the oldest age group in the female population [3,4]. Our results are consistent with these previous American and Korean studies. However, the reason for the decrease in the prevalence of OAB in women aged ≥60 years is not certain.

Our study additionally reported that 24.3% of participants aged ≥40 years had OAB. Castro et al. [13] demonstrated that the prevalence of OAB was 21.5% in respondents aged ≥40 years in Spain. In another study conducted in six European countries, the prevalence in individuals aged ≥40 years was 16.6% [9]. Those studies provide additional evidence that the prevalence increases with age.

When compared with demographically matched controls, participants with OAB reported significantly less work productivity and sexual satisfaction and higher rates of depressive and anxiety symptoms, which is consistent with previous research on the impact of OAB on patient outcomes. LUTS severity has been associated with decreased sexual activity and sexual satisfaction [14]. Although some evidence suggests that sexual dysfunction is higher in men with voiding symptoms [15,16], findings from other studies suggest that erectile dysfunction might be more closely associated with OAB symptoms [17-19]. Our analysis supports decreased sexual satisfaction being associated with OAB. In a population-based prevalence survey, OAB was associated with clinically and statistically higher depression scores, poorer sleep quality and lower levels of overall health-related quality of life [3]. A recent study, which used the HADS to investigate the impact of OAB on mental health, reported that rates of clinically elevated anxiety and depression were markedly higher, particularly among people with bothersome OAB. Irwin et al. also found that OAB was related to greater feelings of depression and stress, as well as compromising patients' working lives [2].

There are several limitations to the present study. One limitation involves the use of self-reports to measure OAB. Evidence indicates that self-reports are vulnerable to inaccuracy relative to the criterion standard of physician diagnosis based on assessment of patient history and urodynamic evaluation [20]. However, measurement of OAB on the basis of a rigorous physician examination would not be feasible in a large-scale, epidemiologic study. Moreover, the use of physician diagnosis would introduce a degree of subjectivity. A second limitation is that the results of self-reported data may be influenced by the mode of administration of the questionnaire; different modes may differ in terms of sampling error, response rates, data completeness, and measurement error [21]. Thus, our data may have been slightly different if collected via mail or face-to-face interviews, and this should be considered when comparing the EPIC studies that collected data via different modalities. However, this limitation is also common to large epidemiologic studies, because there are advantages and disadvantages to each mode of questionnaire administration [21]. Last, many of the questionnaires used for evaluation were specific to OAB, because an objective of this study was to explore the prevalence and impact of OAB. It is possible that the use of less OAB-specific measures would yield a different pattern of results. Future epidemiologic research is needed to explore the possibility of other constellations of LUTS and their relative contribution to patient outcomes.

The medical consultation rate in the present study was low (19.7%), especially considering the rate in studies conducted in other countries (61%) [9]. Our results suggest that many people in Korea were embarrassed by their bladder control problems and were unwilling to talk about such symptoms. Despite the relatively low rate of consultation, 50.7% of those individuals who had OAB symptoms were willing to seek medical consultation. Importantly, of those who did not consult a doctor, many reported that they were unaware that effective treatment was available. Increased public and professional education about problems with bladder control, and that such problems are treatable or at least manageable, is therefore an important goal for the future.

In conclusion, this population-based survey confirmed that OAB symptoms are highly prevalent, and many sufferers appear to have actively sought medical help. Furthermore, OAB has severe effects on daily and sexual life as well as being related to psychological symptoms such as anxiety and depression. Nevertheless, relatively few individuals are currently receiving treatment, and such findings indicate that there is considerable room for improvement.

Notes

This study was supported by grants from Pfizer Korea Ltd.