Voiding Dysfunction after Total Mesorectal Excision in Rectal Cancer

Article information

Abstract

Purpose

The aim of this study was to assess the voiding dysfunction after rectal cancer surgery with total mesorectal excision (TME).

Methods

This was part of a prospective study done in the rectal cancer patients who underwent surgery with TME between November 2006 and June 2008. Consecutive uroflowmetry, post-voided residual volume, and a voiding questionnaire were performed at preoperatively and postoperatively.

Results

A total of 50 patients were recruited in this study, including 28 male and 22 female. In the comparison of the preoperative data with the postoperative 3-month data, a significant decrease in mean maximal flow rate, voided volume, and post-voided residual volume were found. In the comparison with the postoperative 6-month data, however only the maximal flow rate was decreased with statistical significance (P=0.02). In the comparison between surgical methods, abdominoperineal resection patients showed delayed recovery of maximal flow rate, voided volume, and post-voided residual volume. There was no significant difference in uroflowmetry parameters with advances in rectal cancer stage.

Conclusions

Voiding dysfunction is common after rectal cancer surgery but can be recovered in 6 months after surgery or earlier. Abdominoperineal resection was shown to be an unfavorable factor for postoperative voiding. Larger prospective study is needed to determine the long-term effect of rectal cancer surgery in relation to male and female baseline voiding condition.

INTRODUCTION

Colorectal cancer is the third most prevalent cancer in men and in women is second only to breast cancer in the United States [1]. Survival of patients with rectal cancer has improved over the past two decades as a result of earlier diagnosis, radiotherapy and advances in surgical techniques such as total mesorectal excision (TME) [2,3]. Recently, investigations have focused more on combining a cure with improved quality of life for patients after treatment. For urogenital complications, sexual and urinary dysfunction is common complications of rectal cancer surgery [4]. These complications can have a major impact on a patient's physical, psychological, social and emotional functioning, as well as his or her overall well-being [5]. Because the incidence of rectal cancer is highest in the sixth and seventh decades of life, voiding dysfunction can become a more important problem although several western studies demonstrated that sexuality also remains an important aspect at those ages [6,7].

The incidence of voiding dysfunction after rectal cancer surgery currently ranges from 30 to 70% [5,8,9]. Voiding dysfunction after rectal cancer surgery includes empting failure, stress incontinence and urgency, and among them empting failure make up most of the incidences. Difficulty in bladder emptying is generally improved after 3 months, but symptoms that persisted 6 months after surgery are mainly permanent, and long-term dysfunction is reported by 31% of patients [10].

With the introduction of TME, nerve damage was no longer thought to be an inevitable event for rectal cancer surgery because the pelvic autonomic nerves are located just outside the mesorectal fascia, and are therefore not necessarily damaged by the TME procedure. However, voiding dysfunction still remains as one of the common complications after surgery [11].

One of the motives leading to this study is that patients are unlikely to mention voiding problems themselves, either because they are embarrassed or because they do not relate their symptoms to their rectal cancer treatment. We investigated voiding changes and their sequelae after TME in rectal cancer patients.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The total of 50 patients who underwent TME from November 2006 to June 2008 were recruited into this study. At first, this study was part of a prospective study to evaluate voiding function preoperatively and postoperatively. We retrospectively reviewed the data of 50 patients who were available for follow-up after approval by the Institutional Review Board.

Patients with recurrent or metastatic disease, urinary symptomatology (urgency, straining, urinary incontinence, or dysuria) or abnormalities in preoperative uroflowmetry, a history of urinary tract surgery, prior rectal surgery, or no preoperative urodynamic assessment were excluded. The patients' characteristics and interventions performed are listed in Table 1.

All of the operations were performed by two surgeons who were both experts in colorectal surgery. TME was performed according to the principles described by Heald et al. [12], and the pelvic autonomic nerves, including the hypogastric nerve and pelvic splanchnic plexus, were preserved a much as possible in all patients. In the cases of high anterior resection a transection of the mesorectum was performed 5 cm from the tumor, and in low anterior resection and abdominoperineal resection the entire mesorectum was removed.

Three months and 6 months after the operation, all patients underwent a further sequential uroflowmetry and clinical interview with the urologist to detect urinary symptomatology. Particular attention was paid to the presence of straining, urinary incontinence, and urgency.

Patients were instructed to avoid heavy lifting, exercise, and sexual intercourse for a minimum of 4 weeks postoperatively. Less strenuous activities of daily living could be resumed within 1 to 2 weeks. For follow up, patients were educated to visit 1 week later, and every 3 months after the operation. The patients who presented with incontinence in the first visit were educated about and encouraged to perform pelvic floor exercise by a urologic nurse.

The variables investigated included age, sex, type of intervention, clinical stage, parameters of uroflowmetry, and urinary symptomatology. Comparative analysis was conducted by using the Pearson χ2 statistic or Fisher exact test for categorical data, and paired t-test and Wilcoxon signed rank test for investigation of sequential continuous variables. All data were expressed as mean±standard deviation, and SPSS ver. 18.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) software was used for statistical processing. Differences were considered to be significant when P<0.05.

RESULTS

A total of 50 patients recruited in this study including 28 male and 22 female. There were no significant differences in baseline characteristics between the men and the women. The voiding dysfunctions presented by the patients included urgency, straining, urinary incontinence, and dysuria. The most common voiding symptom at 3 months after surgery was straining, which manifested in 19 patients (38.0%). The most common voiding symptom at 6 months after surgery was also straining, which manifested in 8 patients (16.0%). Incontinence was manifested in 13 patients (26.0%) at 3 months after surgery but 5 patients (10.0%) at 6 months after surgery. Rates of all of the voiding dysfunction symptoms decreased 6 months after surgery (Table 2). The overall voiding dysfunction rate at 6 months after surgery was 16.0%. Of the voiding dysfunction symptoms, straining showed a statistically significant difference between low anterior resection and abdominoperineal resection. The abdominoperineal resection group had a higher rate of straining.

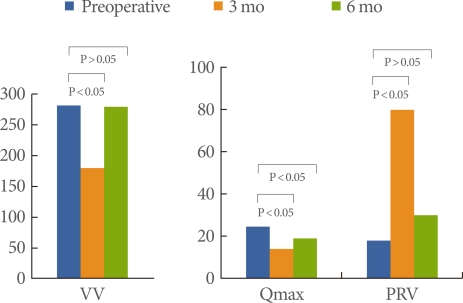

Sequential results of the uroflowmetry parameters are showed in Fig. 1. The preoperative maximal flow rate, voided volume, and post-void residual volume were 24.6±5.2, 288±58, and 19.8±17.0, respectively. At 3 months and 6 months after surgery, these parameters were 14.6±6.2, 188±58, and 79.8±87.0 and 19.6±5.2, 278±58, and 30.8±47.0, respectively. In the comparison of preoperative data with the 6 months data, only the maximal flow rate revealed a significant difference (P<0.05).

Sequential uroflowmetry parameters before and after rectal cancer surgery. VV, voided volume; Qmax, maximal flow rate; PVR, post-void residual volume. Data are analyzed by paired t-test.

When uroflowmetry parameters were compared between low anterior resection and abdominoperineal resection, the patients (n=18) showed unfavorable voiding outcomes (Tables 3, 4). Except for voided volume, maximal flow rate, average flow rate, and post-voided residual volume showed delayed recovery, manifested as lower mean data, in the abdominoperineal resection patients. In the sequential data of the abdominoperinal resection patients, only the maximal flow rate at 6 months after surgery was lower (P=0.02) compared with the preoperative data.

DISCUSSION

In 1979 the TME technique was introduced by Heald. Instead of blind blunt dissection, this technique used sharp dissection under direct vision along pre-existing embryologically determined planes; dividing the visceral fascia surrounding the mesorectum from the pelvic parietal fascia overlying the pelvic floor [12,13]. The TME procedure resulted in improved survival (from 48 to >60%), reduced local recurrence rates (from >20 to <10%), higher incidence of sphincter preservation and reduced blood loss [12,14]. By combining the nerve-preserving principle with the TME procedure, urogenital function remained at normal levels in almost 90% of his patients without compromising oncological outcome [15].

Although the surgical technique has evolved to a high degree, functional outcomes including voiding dysfunction and sexual dysfunction have not been reproduced in larger studies [8,16] Voiding dysfunction after rectal cancer surgery currently ranges from 30 to 70% [5,8,9]. Voiding dysfunction after rectal cancer surgery includes empting failure, stress incontinence and urgency, and among them empting failure makes up most of the incidences. Difficulty in bladder emptying is generally improved after 3 months, but symptoms that persist for 6 months after surgery are mainly permanent and long-term dysfunction is reported by 31% of patients [10].

Early postoperative changes which consist of detrusor hypoactivity and diminished bladder sensation and manifest as urinary retention and overflow incontinence can occur from 1 week to 6 months after surgery [17]. This phenomenon is due to typical effects of parasympathetic nerve damage on voiding. These effects can be transient, if the nerves are not completely divided, they are able to regenerate. Changes that persist for more than 1 year post operatively are mainly permanent, and usually consist of emptying difficulties due to a persistently noncontractile bladder [10]. In our study, the transient decrease in maximal flow rate at 3 months after the operation might be explained by postoperative inflammatory changes in the perivesical tissues and the possible resolution of partial nerve damage with time, resulting in improvement and even complete recovery [17].

Kneist et al. [18] reported a rate of severe voiding dysfunction, defined as the need for a permanent urinary catheter, of 3.8% at hospital discharge and a long-term dysfunction rate of 2.8% in this series. In another series, the rate of voiding dysfunction was 4.1 to 15% at 3 months after surgery, althouth few studies reported the long-term voiding dysfunction rate, which is assumed to be far lower than the rate at 3 months after surgery [19,20]. In our study, overall voiding dysfunction rates at 3 months and 6 months were 38.0% and 16.0%, which is similar to the results of other trials (Table 5).

The only predictive factor for the need to keep a urinary catheter was the failure to preserve or nonvisualization of the autonomic nervous system during the resection [18]. Urinary disorders are more severe when the colonic anastomosis is performed close to the anus [11,19]. Predictive factors for post-operative bladder dysfunction include low rectal cancer (<5 cm from the anal verge), lymph node involvement, and pre-operative urinary dysfunction [19].

Pelvic autonomic nerves can be damaged as a result of failure to identify them, either as a result of lack of anatomical knowledge or simply because of poor visibility owing to bleeding or obesity [21]. The sympathetic nerves are at risk during presacral and ventrolateral dissection of the mesorectum and central arterial ligation, and the parasympathetic nerve supply is especially at risk during deep dissection of the lateral planes. Low rectal cancer increases the risk of combined damage to the pelvic splanchnic nerves and levator ani nerves, due to the small surgical margin deep in the pelvis [22]. Inflammation following anastomotic leakage, dia thermic coagulation, sutures and radiotherapy can cause pelvic nerve damage. Radiotherapy in particular can cause demyelination and affect the autonomic nerves, leading to nerve fibrosis and dysfunction [23]. The Dutch TME trial indicated, however, that radiotherapy does not contribute to the development of urinary dysfunction after rectal cancer treatment when surgical factors are taken into account [10].

Urogenital dysfunction after rectal cancer surgery is mainly dependent on surgical method. Abdominoperineal resection with the construction of a colostomy is associated with an increased incidence of urinary incontinence compared with low anterior resection in which an anastomosis is created [24]. Our study revealed similar results in that the patients with abdominoperineal resection had prolonged voiding dysfunction. The patient group with abdominoperineal resection showed delayed recovery of maximal flow rate and post voiding residual volume.

Effective management of patients with voiding dysfunction after rectal cancer treatment is lacking. Although several treatments have been introduced for voiding dysfunction including pelvic floor exercise and sacral nerve stimulation [25], most of the studies of the treatment of postoperative urogenital dysfunction deal with sexual problems.

Our study had some limitations. The study cohort was small, which resulted in difficulties in analyzing the comparative parameters between males and females. Also we could not determine the effect of neoadjuvant treatment or adjuvant treatment because of the narrow inclusion criteria.

In conclusion, the results of our study imply a favorable outcome of voiding dysfunction at 6 months after surgery. Although the long-term prognosis of voiding dysfunction after surgery is favorable, voiding dysfunction should not be ignored because it is a common phenomenon and it disrupt the quality of life for more than 3 months postoperatively. Postoperative evaluation of patients' voiding outcome should be standard procedure at every follow-up appointment, and available treatment should be proposed if needed. Furthermore, nerve preservation during rectal cancer surgery needs to be given greater emphasis in surgical practice.

Notes

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.