Foreign Bodies in the Urinary Bladder and Their Management: A Single-Centre Experience From North India

Article information

Abstract

Purpose

This study was performed to characterise the nature, clinical presentation, mode of insertion, and management of intravesical foreign bodies in patients treated at our hospital.

Methods

Between January 2008 and December 2014, 49 patients were treated for intravesical foreign bodies at King George Medical University, Lucknow. All records of these patients were retrospectively analysed to characterise the nature of the foreign body, each patient’s clinical presentation, the mode of insertion, and how the case was managed.

Results

A total of 49 foreign bodies were retrieved from patients’ urinary bladders during the study period. The patients ranged in age from 11 to 68 years. Thirty-three patients presented with complaints of haematuria (67.3%), 29 complained of frequency of urination and dysuria (59.1%), and 5 patients reported pelvic pain (10.2%). The circumstances of insertion were iatrogenic in 20 cases (40.8%), self-insertion in 17 cases (34.6%), sexual abuse in 4 cases (8.1%), migration from another organ in 4 cases (8.1%), and assault in 4 cases (8.1%). Of the foreign bodies, 33 (67.3%) were retrieved by cystoscopy, while transurethral cystolitholapaxy was required in 10 patients (20.4%), percutaneous suprapubic cystolitholapaxy was performed in 4 patients (8.1%), and holmium laser lithotripsy was performed in 2 patients (4.08%).

Conclusions

Foreign bodies should always be included in the differential diagnosis when evaluating a patient who presents with chronic lower urinary tract symptoms. A large percentage of foreign bodies can be retrieved using endoscopic techniques. Open surgical removal may be performed in cases where endoscopic techniques are unsuitable or have failed.

INTRODUCTION

Intravesical or intraurethral foreign bodies usually result from iatrogenic injuries, self-insertion, sexual abuse, assault, and migration from adjacent sites, although migration from adjacent sites is rare [1]. Obtaining an accurate history from patients with this condition may be difficult, especially for patients who insert objects for sexual pleasure. A wide range of foreign bodies has been reported in the urinary bladder, including electrical wires, chicken bones, wooden sticks, thermometers, bullets, intrauterine contraceptive devices (IUCDs), encrusted sutures, surgical staples with stones, needles, pencils, household batteries, gauze, screws, pessaries, ribbon gauze, parts of Foley catheters, broken parts of endoscopic instruments, and knotted suprapubic catheters [2-14]. Presentation may be late in many patients because they fear embarrassment. Urinary tract infection, pain, and haematuria are the usual chief complaints [15,16]. The physical examination is usually unremarkable, and routine urine microscopy shows only pus cells and red blood cells. X-ray imaging detects radiopaque foreign bodies, while other foreign bodies are usually detected through ultrasonography. The primary treatment includes careful removal of the foreign body in order to avoid erectile dysfunction in male patients. With advances in endoscopic techniques, open surgery is not usually required, and the majority of cases can be treated using minimally invasive techniques. In this study, we share our 7-year experience of foreign bodies in the bladder.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Between January 2008 and December 2014, 49 patients underwent treatment for intravesical foreign bodies at King George Medical University, Lucknow, Uttar Pradesh, India. The records of these patients were reviewed retrospectively and analysed to characterise the nature of the foreign body, each patient’s clinical presentation, the mode of insertion, and how the foreign body was managed.

RESULTS

A total of 49 foreign bodies were retrieved from patients’ urinary bladders. The patients ranged in age from 11 to 68 years (median age, 36 years). Twenty-eight patients were male and 21 were female, with a male-to-female ratio of 1.3:1. The foreign bodies included lead pencils, ballpoint pens, metallic wire, plastic containers, bullets, copper intrauterine devices, broken parts of Foley catheters, forgotten JJ stents with calculus, wooden sticks, needles, pins, plastic toys, infant feeding tubes, an eraser, the ceramic sheaths of resectoscopes, and prongs of endoscopic removal forceps. Most of the patients presented with haematuria (67.3%), while 29 patients (59.1%) complained of frequency of urination and dysuria, 5 patients reported pelvic pain (10.2%), and 3 patients presented with acute urinary retention (6.1%). The circumstances of insertion were iatrogenic in 20 cases (40.8%), self-insertion in 17 cases (34.6%), sexual abuse in 4 cases (8.1%), migration from another organ in 4 cases (8.1%), and assault in 4 cases (8.1%). Almost all of the cases were treated endoscopically. The types of objects, the causes of injury, and the management strategies are listed in Table 1. Of the foreign bodies, 33 (67.3%) were retrieved by cystoscopy, while transurethral cystolitholapaxy was required in 10 patients (20.4%), percutaneous suprapubic cystolitholapaxy was performed in 4 patients (8.1%), and holmium laser lithotripsy was performed in 2 patients (4.08%). None of the cases required open surgery. The mean follow-up period was 28.3 months (range, 9–36 months). A total of 14 complications were observed in 11 patients, corresponding to a 22.4% incidence rate of postoperative complications. All complications were categorised according to the 5 grades of the Clavien-Dindo classification system [17] (Table 2) and summarised in Table 3. Details regarding the patients (n=11) who developed complications (n=14) are summarised in Table 4.

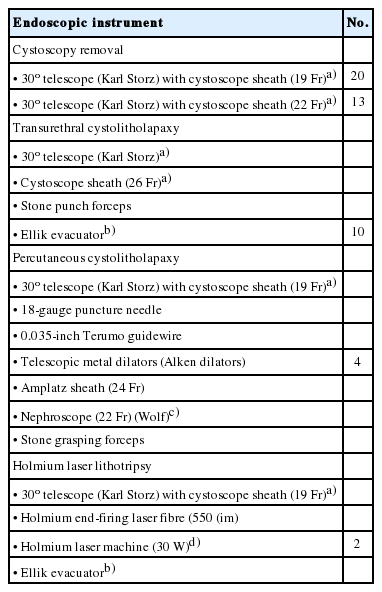

Complications occurring after the removal of foreign bodies in the urinary bladder according to the Clavien-Dindo classification system and their treatment

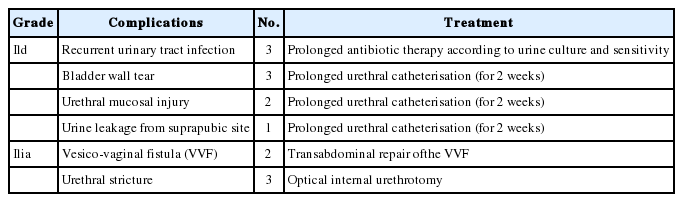

The instruments used in the various endoscopic procedures are listed in Table 5.

DISCUSSION

Foreign bodies can enter into the urinary bladder through iatrogenic mechanisms, migration from adjacent organs, via the urethra, or as a result of trauma. With recent advances in endoscopic urology, many objects such as catheters, stents, and endoscopic instruments are inserted into the urinary tract of patients receiving medical treatment. This has led to an increase in the incidence of iatrogenic foreign bodies. Moreover, self-insertion is also a major contributor to the incidence of foreign bodies in the urinary bladder, and self-insertion is usually performed for sexual gratification [1,15,18,19]. In such cases, the patient often presents late due to feeling embarrassed or humiliated [15,18]. Other cases of self-insertion may be associated with psychiatric disorders such as schizoid personality disorder or borderline personality disorder, intoxication, mental confusion, or sexual curiosity [1,5-21]. Some individuals may insert foreign bodies in order to relieve urinary retention or itching in the urethra [12].

Patients who feel embarrassed may attempt to remove these foreign bodies by themselves. However, this often leads to further migration of the object and injury to the genitourinary tract. Patients may remain asymptomatic or have acute cystitis due to irritation of the lower genitourinary tract, which leads to symptoms such as dysuria, frequency, lower abdominal pain, microscopic or gross haematuria, acute urinary retention, urethral discharge, strangury, and fever [15,16]. Patients often present with anxiety and pain. Suspicion should be high if the patient becomes overly anxious when the sexual history is taken or during the urogenital examination [16]. Surgeons can easily make a diagnosis via a thorough clinical history and a meticulous physical examination. Catheterisation or an attempt to remove the foreign bodies should be carried out only when the exact nature, shape, and location of the object has been determined [18]. This is especially important when objects are located distal to the urogenital diaphragm, where they cannot be palpated directly. Confirmation can be made using a kidney-ureter-bladder radiograph in cases of radiopaque foreign bodies and by ultrasound imaging in cases of radiolucent objects [1,15,16,20,22]. Computed tomography is rarely needed [20]. Urethrocystoscopy is the most accurate method for diagnosing foreign bodies in the urinary bladder.

Treatment should be aimed at removing the foreign object, avoiding complications, and not compromising erectile function in male patients. The method of removing the foreign body should be selected based on the size, nature, and mobility of the object [23]. Removal can be attempted under either regional or general anaesthesia to minimize patient discomfort and movement during the manipulation and retrieval process. If the surgeon thinks that the object can be removed without urethral damage, endoscopic methods should be attempted first [18]. This can be either involve cystoscopy-guided removal using grasping forceps or transurethral cystolitholapaxy using a stone punch. Smaller objects can easily be removed intact, but larger objects require fragmentation. In cases where endoscopic management is not possible, open surgery is recommended. This includes external urethrotomy for objects stuck in the penile urethra and suprapubic cystostomy for intravesical foreign bodies [24,25]. As foreign bodies in the female bladder can be accessed easily via the urethra, they are usually removed endoscopically [10]. However, sharp or large objects may require open removal.

Routine psychiatric evaluation is recommended in patients with foreign bodies in the urethra due to the high incidence of psychiatric disease, mental retardation, and dementia in such patients, although this practice is not universally accepted [1,21,25]. Doing so may reduce the risk of recurrence. Follow-up of these patients is recommended, as they may develop urethral strictures over the course of long-term follow-up.

Removal of intravesical foreign bodies in children is challenging, as the urethra in children is small [16]. This precludes safe endoscopic retrieval. Hence, open surgery is usually the method of choice. The literature reports the removal of foreign bodies in children via a percutaneous technique using direct transurethral visualization [14]. Nephroscopes have been used transurethrally for the retrieval of screws as well as magnetic retrievers for galvanic objects [15]. Additionally, holmium: yttrium-aluminium-garnet lasers have also been used to cut and remove foreign bodies from the bladder [26].

Parts of Foley catheters, such as the tip and balloon, have been found in the bladder on many occasions [12]. In our study, parts of Foley catheters were found in 7 patients, who had a previous history of transurethral resection of the prostate (4 patients), transurethral resection of a bladder tumour (1 patient), or open prostatectomy (2 patients). Forgotten double J stents may present with stone formation or encrustations, which make their removal difficult. In our study, forgotten JJ stents with encrustations were found in 8 patients; the stents had been inserted after percutaneous nephrolithotomy (6 patients) or ureteroscopic stone retrieval (2 patients) (Fig. 1). Cystoscopic removal was possible in 1 patient, while 4 required transurethral cystolitholapaxy, 2 needed holmium laser lithotripsy, and 1 required percutaneous suprapubic cystolitholapaxy due to the large bulk of the stone accretion over the JJ stent.

Pelvic (A, B) and kidney-ureter-bladder (C) X-rays showing a forgotten JJ stent with encrustation and stone formation.

The factors associated with forgotten JJ stents were low socioeconomic status (n=4), low educational status (n=2), and incomplete information provided to the patients (n=2). In order to reduce the incidence of forgotten JJ stents, we place a special emphasis on patient education regarding timely stent removal. An abdominal X-ray of every patient is performed in whom a stent is inserted and given to them to ensure that they are aware of the presence of the stent. We have developed a patient information system through which we remind patients when their stent must be removed.

Although extremely rare, foreign bodies may perforate and enter the bladder from adjacent organs, such as the gastrointestinal tract or the female genital tract. A small percentage of IUCDs may perforate and enter the urinary bladder. This can occur at the time of their insertion or due to slow migration into the bladder through the uterine wall [7]. Thereafter, encrustation or stone formation over the IUCD may occur. In our study, we endoscopically retrieved 4 IUCDs with encrustations from the bladder (Fig. 2).

(A) Coronal reformatted noncontrast computed tomography image showing intrauterine contraceptive device in the bladder. (B) Three-dimensional reconstructed computed tomography image showing the same device as in panel A.

Trauma may also serve as a mechanism for the entry of foreign bodies into the urinary bladder. Bullets, pieces of shells, and splinters can be found in such cases. Bullets are able to remain in the urinary bladder without causing significant symptoms [6]. In our study, bullets were found in 3 patients who had been shot. In all 3 patients, the intact bullet was retrieved through percutaneous cystolitholapaxy. A transverse incision (approximately 1 cm) was made 2 cm above the pubic symphysis. Through this incision, an 18-gauge puncture needle was passed into the bladder under transurethral 19-Fr cystoscopic guidance. A Terumo guide wire (0.035 inch) was then passed through the puncture needle, after which dilatation of the tract was performed using telescopic metal dilators (Alken dilators) and a 24-Fr Amplatz sheath was placed. A nephroscope (22 Fr) was inserted through the Amplatz sheath and the bullet was retrieved by stone-grasping forceps (Figs. 3, 4). Transurethral and suprapubic catheters were placed at the end of the procedure. The suprapubic catheter was removed on postoperative day 1, and the urethral catheter was removed on postoperative day 2.

An X-ray of the pelvis (A) and computed tomography (axial section) (B, C) showing a bullet in the urinary bladder (marked with a red arrow).

Percutaneous cystolitholapaxy technique. (A) Under transurethral 19-Fr cystoscopic guidance, a suprapubic tract was made with telescopic metal dilators (Alken dilators) (yellow arrow), and a 24-Fr Amplatz sheath was placed (blue arrow). (B) The bullet was visualised with a 22-Fr nephroscope through the percutaneous tract. (C) The bullet was retrieved using stone-grasping forceps (red arrow). (D) The bullet after removal.

The self-insertion of foreign bodies into the urethra for sexual gratification has also been reported. This is more common in females, because the urethra is short. Various types of objects can be introduced into the bladder via the urethral route. We cystoscopically retrieved a lead pencil from 2 patients and a ballpoint pen from 2 patients; these objects had been self-inserted for sexual stimulation (3 patients) or as part of sexual abuse (1 patient) (Fig. 5). Long wires have also been found in the bladder after either being inserted through the urethra either nonconsensually or through self-insertion [25,27]. Stravodimos et al. [25] reported the case of a 53-year-old male who introduced an electrical wire into his urethra for masturbation, which was removed by suprapubic cystostomy after a failed attempt to retrieve it through the urethra. In our study, 2 patients had a metallic wire in the bladder. Cystoscopic removal was possible in one, while the other required transurethral cystolitholapaxy due to the presence of a complex knot in the wire. In our study, a plastic container was found in the bladder in 2 females; in these cases, the container was self-inserted for sexual gratification and was removed by transurethral cystolitholapaxy (Fig. 6).

(A) Axial computed tomography (CT) image showing a pen in the urinary bladder reaching up into the anterior abdominal wall. (B) Axial CT image showing the same pen piercing the left posterior bladder wall.

A total of 14 complications were observed in 11 patients, with a 22.4% incidence rate of postoperative complications. Although the incidence of complications appears high, an analysis of the complications according to the Clavien-Dindo classification system demonstrates that most of the complications were minor and would be unlikely to be reported in the absence of a standardized reporting system [28]. Of the 4 patients in whom an IUCD was retrieved from the bladder, a vesico-vaginal fistula (VVF) occurred in 2 patients postoperatively. These patients underwent successful transabdominal VVF repair. In the remaining 2 patients, spontaneous healing of the bladder tear occurred with prolonged urethral catheterisation (2 weeks). Urethral stricture disease was identified in 3 patients on retrograde urethrograms (Fig. 7), and these patients were treated successfully with optical internal urethrotomy. The true incidence of urethral strictures is probably higher, as some patients may fail to return for follow-up visits. The patient should be made aware of this complication preoperatively. It should also be emphasized that the primary risk factor for urinary strictures is the insertion of the foreign body, and not its retrieval [18].

Encrustation and stone formation often occur on foreign bodies in the bladder and the surgeon must be extremely careful to avoid urethral and bladder mucosal injuries during their removal. Endoscopic removal is usually associated with less morbidity and shorter hospital stays. Open surgery is rarely required due to the advent of modern endoscopic instruments. In conclusion, foreign bodies should always be included in the differential diagnosis when assessing a patient who presents with chronic lower urinary tract symptoms. The method of choice for removing foreign objects depends upon the nature and location of the foreign body, the patient’s condition and age, and the surgical skills of the operating surgeon. A large number of foreign bodies can be retrieved using minimally invasive endoscopic techniques. Open surgical removal is usually performed in cases where minimally invasive techniques are unsuitable or have failed.

Notes

Research Ethics

This study was performed according to the Helsinki Declaration (http://www.wma.net/en/30publications/10policies/b3/) and was approved by the Institutional Ethical Committee of King George Medical College (IEC: 92/2014). Written informed consent was obtained from all subjects.

Conflict of Interest

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the cooperation of the residents of the Urology Department of King George Medical University who participated in patient appointments and follow-up. We also appreciate the commitment and compliance of the patients who provided us with the requisite information and attended regular follow-up visits.