Long-term Surgical and Chemical Castration Deteriorates Memory Function Through Downregulation of PKA/CREB/BDNF and c-Raf/MEK/ERK Pathways in Hippocampus

Article information

Abstract

Purpose

Goserelin is a drug used for chemical castration. In a rat model, we investigated whether surgical and chemical castration affected memory ability through the protein kinase A (PKA)/cyclic adenosine monophosphate response element-binding protein (CREB)/brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) and c-Raf/mitogen-activated protein kinases-extracellular signal–regulated kinases (MEK)/extracellular signal–regulated kinases (ERK) pathways in the hippocampus.

Methods

Orchiectomy was performed for surgical castration and goserelin acetate was subcutaneously transplanted into the anterior abdominal wall for chemical castration. Immunohistochemistry was done to quantify neurogenesis. To assess the involvement of the PKA/CREB/BDNF and c-Raf/MEK/ERK pathways in the memory process, western blots were used.

Results

The orchiectomy group and the goserelin group showed less neurogenesis and impaired short-term and spatial memory. Phosphorylation of PKA/CREB/BDNF and phosphorylation of c-Raf/MEK/ERK decreased in the orchiectomy and goserelin groups.

Conclusions

Short-term memory and spatial memory were affected by surgical and chemical castration via the PKA/CREB/BDNF and c-Raf/MEK/ERK signaling pathways.

• HIGHLIGHTS

- Surgical and chemical castration decreased neurogenesis and impaired short-term and spatial memory.

- Phosphorylation of the PKA/CREB/BDNF pathway decreased after surgical castration and chemical castration.

- Phosphorylation of the c-Raf/MEK/ERK pathway decreased after surgical castration and chemical castration.

INTRODUCTION

Chemical castration using luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone (LHRH) agonists is an alternative method to surgical castration. Goserelin, a synthetic long-acting agonist of LHRH, has been used in the treatment of prostate cancer, metastatic breast cancer, and uterine fibromas. This agent has similar effects to surgical castration [1]. Chronic orchiectomy has been found to result in deficits in spatial learning, which were reversed by testosterone replacement at physiological levels [2]. It was also reported that surgical castration of male rats impaired their performance on a working memory task during acquisition of an 8-arm maze task [3].

Newly formed neurons in the hippocampus play a significant role in hippocampal-dependent learning and memory [4]. Removal of testicular hormones by castration reduces the number of newly generated neurons in adult rodents, leading to a decline in memory [5,6]. Testosterone enhances neurogenesis in adult animals, while in contrast, low testosterone decreases hippocampal neurogenesis and neuronal survival [5]. Testosterone deprivation impairs spatial working memory and cognitive function in male rats [7].

The category of neurotrophins includes brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), nerve growth factor, neurotrophin-3 (NT-3), NT-4/5, NT-6, and NT-7. Of these, BDNF is known to be responsible for neurogenesis, neuroprotection, and synaptic plasticity [8]. Cyclic adenosine monophosphate response element-binding protein (CREB) acts as a transcription factor and plays an important role in neuronal survival, neurogenesis, and synaptic plasticity. Increased phosphorylated CREB (p-CREB) expression leads to increased activation of protein kinase A (PKA) [9]. The CREB signal, including BDNF, controls the expression of genes that promote synaptic and neuronal plasticity [10]. CREB-BDNF signaling has been associated with many neurobiological phenomena, including cell survival and synaptic plasticity [11]. In the hippocampus, the PKA-CREB-BDNF pathway has been suggested to be closely associated with cognitive function [12]. We sought to explore the relationship between cognitive function after castration and the PKA-CREB-BDNF signaling pathway.

Mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPKs), including serine and threonine protein kinases, are involved in synaptic plasticity, learning, and memory [13]. Of these, extracellular signal–regulated kinases (ERKs) are activated by c-Raf serine/threonine kinases. c-Raf activates MAPK-ERK kinase (MEK), which then activates ERK1/2 [14]. The c-Raf/MEK/ERK pathway has been suggested to play a crucial role in the hippocampal memory acquisition process [15]. Therefore, we also sought to explore the relationship between memory processes after castration and the c-Raf/MEK/ERK signaling pathway.

PKA/CREB/BDNF and c-Raf/MEK/ERK signaling is closely related to memory formation processes. In a rat model, we investigated whether surgical and chemical castration influenced memory capability through the PKA/CREB/BDNF and c-Raf/MEK/ERK pathways in the hippocampus.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals Treatments

The Institutional Animal Care and Ethics Committee (KHUASP [SE]-18-150) of Kyung Hee University reviewed and approved this experimental procedure. Male Sprague-Dawley rats were purchased commercially (Orient Co., Seoul, Korea); their weight was 300±10 g and their age was 8 weeks. The rats were equally divided into 3 groups: the sham-operation group, the orchiectomy group, and the goserelin group (n=10 in each group).

Surgical Castration

Bilateral orchiectomy was performed as described elsewhere [16]. Briefly, using 3% isoflurane in 20% O2 and 77 % N2, the rats were anesthetized. After an incision was made on the center of the scrotum, the arteries, veins, and ductus deferens were isolated, ligated, and severed. We removed the testicles and epididymis in the same manner.

Chemical Castration with Goserelin

Goserelin acetate in a biodegradable cylinder (1 mm wide ×5 mm long, 3.6 mg) (Zoladex, AstraZeneca, Bedfordshire, UK) was subcutaneously transplanted into the anterior abdominal wall of the rats in the goserelin treatment group. The transplantation of goserelin was repeated 3 times at intervals of 4 weeks, and the total application of the drug lasted 84 days.

Step-Down Avoidance Test

Following a previously described method [17], the step-down avoidance test was conducted to assess short-term memory. Eighty-three days after the start of the experiment, the rats were placed on a 7×25-cm platform and the time taken for them to descend was measured. The platform faced a 42×25-cm grid, and stainless steel bars measuring 0.1 cm in diameter were placed 1 cm apart at a height of 2.5 cm. Twenty-four hours before determining latency, the animals were immediately shocked with a 0.5-mA scramble for 3 seconds as they reached the ground. The latency time was determined 24 hours after the training session. Latency was defined as the time interval between the time the rat descended and when its four legs were placed on the grid. A latency time of 5 minutes or longer was considered as 5 minutes.

Eight-Arm Radial Maze Test

Following methods described elsewhere [18], the eight-arm radial maze test was conducted 82 days after the start of the experiment. Starting 24 hours before the test, the rats were deprived of water. The maze consisted of an octagonal stage with eight arms, which were 50 cm long and 10 cm wide. A water cup measuring 1 cm in depth and 3 cm in diameter was placed at the end of each of the eight arms. The maze was placed 1 m above the floor. When the rat had drunk all of the water in the 8 arms, or when more than 5 minutes had elapsed in the experiment, then the test was completed. Re-entering a previously visited arm was considered to be an error, and the error number was tabulated. The number of correct choices before the first error was recorded as the correct number.

Testosterone Detection

From a cardiac puncture, blood from each rat was collected and assayed for serum testosterone. A SpectraMax 190 enzymelinked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) reader (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA, USA) was used at a wavelength of 450 nm, with commercially available testosterone ELISA kits (IBL International GmbH, Hamburg, Germany).

Tissue Preparation

Zoletil 50 (10 mg/kg, intraperitoneally; Vibac Laboratories, Carros, France) was used to induce anesthesia, and then the rats received a transcardial perfusion of 50mM phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). Next, the rats were infused with a solution containing 4% paraformaldehyde in 100mM phosphate buffer (pH, 7.4). After that, fixed brains were cryoprotected in a 30% sucrose solution for 3 days, and the sections were cut into 40-μm coronal sections using a freezing microtome (Leica, Nussloch, Germany). On average, eight sections including the hippocampus were obtained.

BrdU Immunohistochemistry

Following a previously described method [18], 5-bromo-2′-deoxyuridine (BrdU) immunohistochemistry was carried out. First, the sections were infiltrated with 0.5% Triton X-100 in PBS for 20 minutes, and then they were pretreated with 50% formamide-2 X standard saline citrate for 2 hours at 65℃. Next, the sections were incubated with 2 N HCl for 1 hour, neutralized with 0.1M sodium borate buffer (pH, 8.5) for 30 minutes, and treated with mouse monoclonal anti-BrdU primary antibody (1:600, Roche Applied Science, Mannheim, Germany) at 4℃ overnight. After washing 3 times, these sections were treated with a biotinylated mouse secondary antibody (1:200; Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA, USA) for 1 hour, followed by treatment with avidin–peroxidase complex (1:100; Vector Laboratories) for 1 hour. The sections were then visualized in 50mM Tris-HCl (pH, 7.6) containing 0.03% hydrogen peroxide, 0.03% 3,3′-diaminobenzidine (DAB), and 40-mg/mL nickel chloride for immunostaining.

The same sections were counterstained using mouse antineuronal nuclei antibody (1:300; Chemicon International, Temecula, CA, USA). After washing 3 times, the sections were treated with a biotinylated mouse secondary antibody (1:200; Vector Laboratories) for 1 hour, followed by another hour of treatment with avidin-peroxidase complex (1:100; Vector Laboratories) at 4℃. These slides were dehydrated by alcohol and mounted using Permount coverslips (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., Fair Lawn, NJ, USA).

DCX Immunohistochemistry

Following a method described elsewhere [18], doublecortin (DCX) immunohistochemistry was performed. After the sections were incubated in 3% H2O2 for 30 minutes at room temperature, they were blocked by 10% normal rabbit serum in PBS with 0.2% Triton X-100 and 1% bovine serum albumin for 1 hour. The section was incubated in goat anti-DCX antibody (1:500; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA, USA) at 4℃ overnight. After washing 3 times, the sections were treated with a biotinylated goat secondary antibody (1:200; Vector Laboratories) for 1 hour, followed by another hour with avidin–peroxidase complex (1:100; Vector Laboratories). The sections were visualized in 50mM Tris-HCl (pH, 7.6) containing 0.03% hydrogen peroxide and 0.03% DAB for immunostaining. The slides were dehydrated by alcohol and mounted using Permount coverslips (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc.).

Western Blot Analysis

Following a method described elsewhere [18], western blotting analysis was conducted. The hippocampal tissues were homogenized in lysis buffer (1% Triton X-100, 150mM NaCl, 10% glycerol, 100mM sodium fluoride, 1mM sodium orthovanadate, 1mM PMSF [phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride], 1.5mM MgCl2 ·6H2O, 1mM EGTA [ethyleneglycol-bis-(b-aminoethylether)- N,N,N’,N’-tetraacetic acid], and 50mM HEPES [N-2-hydroxyethylpiperazine-N-2-ethanesulfonic acid]). After centrifugation for 15 minutes at 4℃ (14,000 rpm), the supernatant was collected. Using a Bio-Rad protein assay kit (Hercules, CA, USA), protein content was measured. Protein (40 μg) was electrophoresed on sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis gel, and then transferred to nitrocellulose membranes. The membranes were blocked with 5% skim milk powder at 4℃ for 1 hour, and then treated with mouse actin antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology; 1:500), rabbit BDNF antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology; 1:1,000), rabbit tropomyosin receptor kinase B (TrkB) antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology; 1:1,000), rabbit total PKA antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology; 1:1,000), rabbit p-PKA antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology; 1:1,000), rabbit total c-Raf antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology; 1:1,000), rabbit p-c-Raf antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology; 1:1,000), rabbit total MEK 1/2 antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology; 1:1,000), rabbit p-MEK 1/2 antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology; 1:1,000), rabbit total ERK 1/2 antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology; 1:1,000), p-ERK 1/2 antibody (1:1, 000; Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA, USA). The membranes were treated with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary rabbit antibody (1:2,000) at room temperature for 1 hour. Bands were visualized using an enhanced chemiluminescence detection system (Santa Cruz Biotechnology).

Data Analysis

After determining the area of the hippocampal dentate gyrus using the Image-Pro Plus image analyzer (Media Cybernetics Inc., Silver Spring, MD, USA), the numbers of BrdU-positive and DCX-positive cells were expressed as the numbers of cells per square millimeter of the granular cell layer in the hippocampal dentate gyrus. Bands were densitometrically quantified using ImagePro Plus software (Media Cybernetics) to compare protein expression levels.

The results are presented as the mean±standard error of the mean. One-way analysis of variance and the Duncan post hoc test were performed for comparisons among the groups. P-values<0.05 were considered to indicate statistical significance.

RESULTS

Testosterone Concentration

Data on testosterone concentration are shown in Fig. 1. Serum concentrations of testosterone were lower in the orchiectomy group and in the goserelin group than in the sham-operation group (P<0.05).

Short-term Memory

Fig. 2A presents data on the latency time of the step-down avoidance task. The latency time was shorter in the orchiectomy group and in the goserelin group than in the sham-operation group (P<0.05).

Effects of surgical and chemical castration on short-term memory and spatial memory. (A) Latency in the step-down avoidance test. (B) The time required to accomplish eight successful performances. (C) The number of errors made before eight successful performances. SH, sham-operation group; ORX, orchiectomy group; GOS, goserelin group. *P<0.05 compared to the sham-operation group.

Spatial Memory

Fig. 2B and C show the correct choice number and error number from the 8-arm radial maze task. The rats in the orchiectomy group and in the goserelin group showed higher error numbers than those in the sham-operation group (P<0.05). The correct number, in contrast, exhibited no significant differences among the 3 groups.

Neurogenesis

Fig. 3 presents photomicrographs of BrdU-positive cells and DCX-positive cells in the hippocampal dentate gyrus. Hippocampal neurogenesis was suppressed in the orchiectomy group and in the goserelin group relative to the sham-operation group (P<0.05). DCX-positive cells were suppressed in the orchiectomy group and in the goserelin group relative to the sham-operation group (P<0.05).

Effects of surgical and chemical castration on cell proliferation and doublecortin (DCX) expression in the hippocampal dentate gyrus. (A) Photomicrographs of 5-bromo-2′-deoxyuridine (BrdU)-positive cells. The scale bar represents 100 μm. (B) Photomicrographs of DCX-positive cells. The scale bar represents 100 μm. (C) The number of BrdU-positive cells in the hippocampal dentate gyrus. (D) The number of DCX-positive cells in the hippocampal dentate gyrus. SH, sham-operation group; ORX, orchiectomy group; GOS, goserelin group. *P<0.05 compared to the sham-operation group.

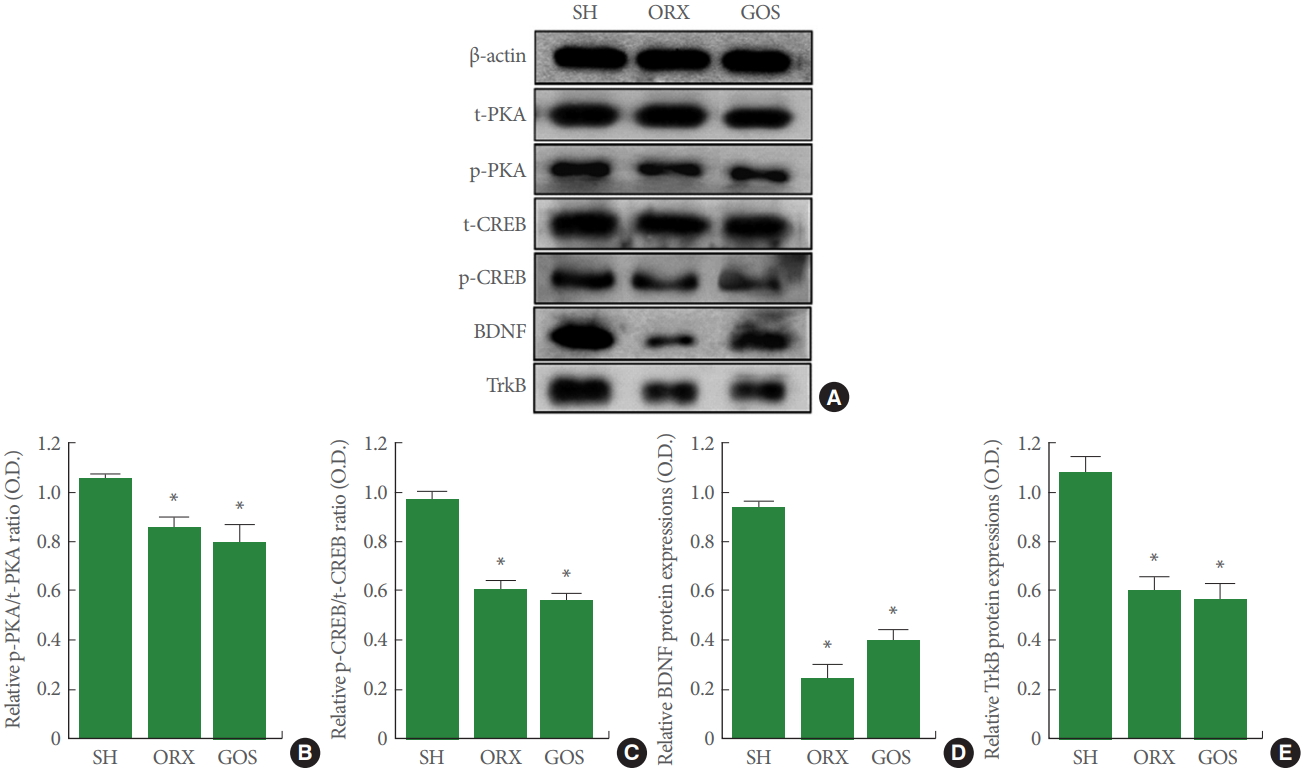

BDNF, TrkB, p-PKA, p-CREB Expressions in Hippocampus

Fig. 4 shows the relative expression levels of BDNF, TrkB, p-PKA, and p-CREB in the hippocampus. The expression of BDNF, TrkB, p-PKA, and p-CREB was suppressed in the orchiectomy group and in the goserelin group relative to the shamoperation group (P<0.05 for all).

Effects of surgical and chemical castration on the expression of PKA-CREB-BDNF signaling in the hippocampus. (A) Representative western blot images of PKA, CREB, BDNF, and TrkB. (B) Ratio of phosphorylated PKA (p-PKA) to total PKA (t-PKA). (C) Ratio of phosphorylated CREB (p-CREB) to total CREB (t-CREB) (D) Relative expression levels of BDNF. (E) Relative expression levels of TrkB. PKA, protein kinase A; CREB, cyclic adenosine monophosphate response element-binding protein; BDNF, brain-derived neurotrophic factor; TrkB, tropomyosin receptor kinase B; SH, sham-operation group; ORX, orchiectomy group; GOS, goserelin group. *P<0.05 compared to the sham-operation group.

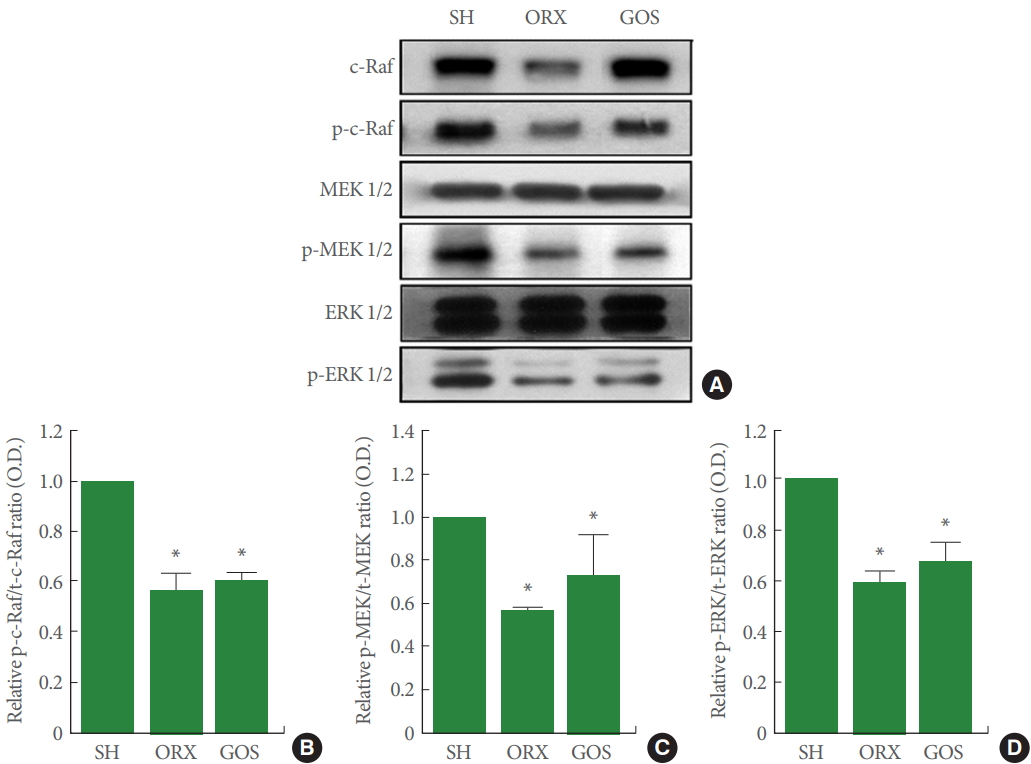

p-c-Raf, p-MEK, p-ERK Expression in Hippocampus

Fig. 5 shows the relative expression levels of p-c-Raf, p-MEK, and p-ERK in the hippocampus, all of which were suppressed in the orchiectomy group and in the goserelin group relative to the sham-operation group (P<0.05 for all).

Effects of surgical and chemical castration on the expression of c-Raf/MEK/ERK signaling in the hippocampus. (A) Representative western blot images of c-Raf, MEK, and ERK. (B) Ratio of phosphorylated c-Raf (p-c-Raf) to total c-Raf (t-c-Raf). (C) Ratio of phosphorylated MEK 1/2 (p-MEK 1/2) to total MEK 1/2 (t-MEK 1/2). (D) Ratio of phosphorylated ERK 1/2 (p-ERK 1/2) to total ERK 1/2 (t-ERK 1/2). MEK, mitogen-activated protein kinases-extracellular signal–regulated kinases; ERK, extracellular signal–regulated kinases; SH, sham-operation group; ORX, orchiectomy group; GOS, goserelin group. *P<0.05 compared to the sham-operation group.

DISCUSSION

Plasma testosterone mainly originates in the testicles, and orchiectomized rats have been shown to have very low testosterone levels. LHRH agonists cause chemical castration equivalent to surgical castration [19]. In the current study, testosterone levels were similarly low in goserelin-treated and orchiectomized rats.

Beer et al. [20] reported that prostate cancer treatment resulted in androgen deficiency, leading to long-term memory impairment. Cognitive deficits can be a symptom of orchiectomy, which is associated with a decrease in the expression of hippocampal androgen receptors [21]. In the current study, orchiectomy and goserelin treatment reduced short-term memory and worsened spatial memory.

The hippocampus is a target of androgen action, as testosterone improves hippocampal neurogenesis through an androgendependent mechanism [5]. Orchiectomy-induced reduction of testicular hormone levels leads to a decrease in new cell formation in the hippocampus [5,6]. Testosterone supplementation, in contrast, improves the castration-induced decrease in new cell formation [5,6]. In the current study, orchiectomy and goserelin treatment suppressed new cell formation in the hippocampal dentate gyrus.

Activation of the CREB cascade is regulated by PKA, ERK, and phosphatidylinositol-3 kinase [22]. Inhibition of CREB decreased neurogenesis and hippocampal plasticity, whereas expression of CREB may contribute to the number of new neurons and memory ability [23]. The downstream actions of CREB involve effects on synaptic plasticity and hippocampaldependent long-term memory [24]. PKA can directly activate CREB by phosphorylation of CREB [25]. In the adult brain, CREB participates in neuronal plasticity and potentiates learning and memory processes [26]. Learning and memory capacity is known to be enhanced through the PKA-CREB-BDNF signaling pathway [27]. In the current study, orchiectomy and goserelin reduced the level of phosphorylated PKA-CREBBDNF signaling. These results indicate that orchiectomy or goserelin treatment exacerbates memory impairment by reducing PKA/CREB/BDNF/signaling.

The most important upstream activator of c-Raf-MEK-ERK is the Raf protein [14]. Phosphorylation of c-Raf at threonine and serine residues activates c-Raf, which in turn activates MEK. Furthermore, activated MEK activates MAPK. The MAPK pathway is a series of intracellular phosphorylation cascades that play important roles in transducing extracellular stimuli, ultimately leading to cell differentiation, proliferation, survival, or death [28]. The ERK signaling pathway modulates hippocampal-dependent learning and long-term synaptic plasticity [29]. MAPK/ERK activation is necessary for memory consolidation and synaptic plasticity [30].

The ERK pathway is a major signaling pathway within the MAPK signaling pathway. Activation of ERK has been strongly implicated in the differentiation, survival, and adaptive responses of neurons during development and in the adult brain [31]. MAPKs regulate the transcription of specific genes through activation of the transcription factor CREB [32]. In the present study, orchiectomy and goserelin inhibited the levels of phosphorylated c-Raf, MEK 1/2, and ERK 1/2. These results indicate that orchiectomy or goserelin treatment exacerbates memory impairment by reducing the phosphorylation of c-Raf/MEK/ERK.

Downregulation of the PKA/CREB/BDNF and c-Raf/MEK/ERK pathways may result in reduced neurogenesis, which is an important mechanism underlying the spatial memory dysfunction caused by long-term surgical and chemical castration.

Notes

Fund/Grant Support

This research was supported by the grants from the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF-2013R1A1A1063509).

Research Ethics

The experimental procedure was approved by the Kyung Hee University Institutional Animal Care and Ethics Committee (KHUASP[SE]-18-150).

Conflict of Interest

KHK, an associate editor of International Neurourology Journal, is the corresponding author of this article. However, he played no role whatsoever in the editorial evaluation of this article or the decision to publish it. Except for that, no potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTION STATEMENT

·Full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis: SMS, CJK

·Study concept and design: SMS, KHK

·Acquisition of data: TWK, SSP, IGK

·Analysis and interpretation of data: MK, SYR

·Drafting of the manuscript: SMS

·Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: CJK

·Statistical analysis: TWK, SSP, IGK

·Administrative, technical, or material support: MK, SYR

·Study supervision: CJK, KHK