The Effects of Intradetrusor BoNT-A Injections on Vesicoureteral Reflux in Children With Myelodysplasia

Article information

Abstract

Purpose

We retrospectively evaluated the efficacy of botulinum neurotoxin A (BoNT-A) on vesicoureteral reflux (VUR), continence status, and urodynamic parameters in children with myelodysplasia who were not responsive to standard conservative therapy.

Methods

The study included 31 children (13 boys, 18 girls) with a mean age of 9.2±2.3 years (range, 5–14 years) with myelodysplasia, retrospectively. All children were fully compatible with clean intermittent catheterization (CIC) and did not respond to the maximum tolerable anticholinergic dose. All children received an intradetrusor injection of 10 U/kg (maximum, 300 U) of BoNT-A into an infection-free bladder. All patients had VUR (22 unilateral, 9 bilateral) preoperatively. The grade of reflux was mild (grades 1, 2), intermediate (grade 3), and severe (grades 4, 5) in 25, 7, and 8 ureters, respectively.

Results

The mean maximum bladder capacity increased from 152.9±76.9 mL to 243.7±103 mL (P<0.001), and the maximum detrusor pressure decreased from 57±29.4 cm H2O to 29.6±13.9 cm H2O (P<0.001). After BoNT-A treatment, 16 refluxing ureters (40%) completely resolved, 17 (42.5%) improved, 5 (12.5%) remained unchanged, and 2 (5%) became worse. Of the 31 children with urinary leakage between CICs, 22 (71%) became completely dry, 6 (19%) improved, and 3 (10%) experienced partial improvement.

Conclusions

In children with myelodysplasia, we were able to increase bladder capacity, enhance continence, and prevent VUR by using intradetrusor BoNT-A injections. Although our results are promising, a larger group of long-term prospective studies are warranted to investigate this method of treatment.

INTRODUCTION

Vesicoureteral reflux (VUR) is a common problem that affects 15%–50% of patients with neurogenic bladder (NB) [1]. It is an important risk factor for renal scarring and may be caused by an anatomically defective ureterovesical junction or by a normal ureterovesical junction mechanism that is overwhelmed by increased detrusor pressure, as in NB. In NB, VUR depends more on increased bladder pressure or chronic infections, bladder trabeculations, and diverticula, which may disrupt the valve mechanism [2-4]. Children with NB may have high detrusor pressures due to a dyssynergic external sphincter and poor bladder compliance. The cornerstone of reflux management in these cases of NB is to reduce the detrusor pressure. If the bladder pressure decreases, the reflux can resolve spontaneously. The aim of treatment is to eliminate urinary tract infections and to protect kidney function. Initial treatment in NB begins with clean intermittent catheterization (CIC) and anticholinergic treatment, which can lead to spontaneous resolution in 43%–58% of cases [5,6]. However, a significant proportion of children do not achieve a satisfactory therapeutic effect through these modalities, or treatment is discontinued due to the adverse effects of treatment [7]. If there is no response to these treatments, ureteric reimplantation with or without bladder augmentation has proved to be successful in NB, as in normal bladders [1]. Second-line treatments include minimally invasive procedures such as botulinum neurotoxin A (BoNT-A) injections and neuro-stimulation [8]. In clinical use, BoNT-A treatment has been shown to be well-tolerated and effective, with rare systemic adverse effects [9]. The precise mechanism underlying the efficacy of BoNT-A injections remains unknown. Many studies have shown that detrusor pressure decreases and bladder capacity increases after BoNT-A treatment [10-12]. In this study, we reviewed our experience of managing children with NB due to myelodysplasia with VUR who did not respond to conservative treatment and evaluated the effects of BoNT-A treatment on VUR in this group of children. The primary outcome was to determine the VUR status through voiding cystourethrography before and 6 weeks after BoNT-A injections. The secondary outcomes were continence status and urodynamic parameters.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The files of 31 children with myelodysplasia who underwent BoNT-A treatment due to high detrusor pressure despite anticholinergic treatment and CIC use between 2012 and 2019 were evaluated retrospectively. Thirty-one children had VUR in 40 ureters (22 unilateral and 9 bilateral VUR) before the treatment. According to the system introduced in an international study of reflux, reflux was mild in 25 ureters (grades 1 and 2 at a score of 5 points), moderate (grade 3) in 7 ureters, and severe (grades 4 and 5) in 8 ureters [13]. BoNT-A injections (10 U/kg, diluted with 0.9% NaCl, with a maximum dose of 300 U) were made into the bladder base and dome under general anesthesia, with 20 to 30 injections performed depending on the total dose under rigid cystoscopic guidance. The base of the bladder was not preserved. Although the need for BoNT-A injections ranged from 6 months to 1 year, reflux responses were evaluated only after the first BoNT-A injection in our study. Before and 6 weeks after BoNT-A treatment, continence status was assessed and cystograms, urinary ultrasound, and urodynamic examinations were performed. The definition of hydronephrosis included all grades (1–4) of the Society for Fetal Urology. For urodynamic studies, a computerized system (Locum Wireless Urodynamic System; Aymed, Istanbul, Turkey) was used. The formulation used for BoNT-A treatment was Botox (Allergan, Irvine, CA, USA). The intradetrusor BoNT-A injections were applied using a technique similar to that described in our previous study [10].

The inclusion criteria were as follows: failure or inability to tolerate oral anticholinergic therapy, CIC use, and having NB due to myelodysplasia and VUR prior to BoNT-A injection. The exclusion criteria were having previous bladder surgery and current treatment with endovesical pharmacologic agents.

Statistical Analysis

The normality of distribution of the parameters was evaluated using the Shapiro-Wilk test. The paired-sample t-test was used to compare normally distributed parameters, and the Wilcoxon signed-rank test was used to compare parameters that did not show a normal distribution. Cross-tabulation was used to show the distribution of VUR and hydronephrosis. The McNemar test was used to compare qualitative data.

RESULTS

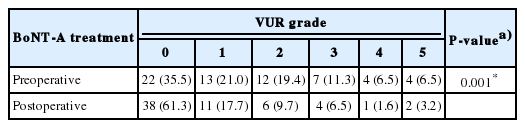

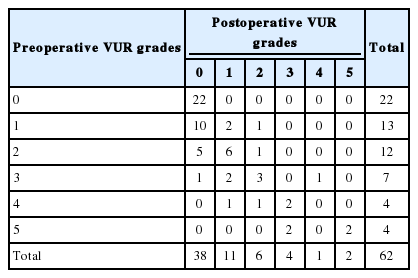

Thirty-one children with myelodysplasia were treated with BoNT-A injections between 2012 and 2019. The children had VUR before BoNT-A treatment. The mean age of these 31 children (13 boys, 18 girls) was 9.2±2.3 years (range, 5–14 years). All children were found to have used CIC and anticholinergics before BoNT-A injections; they were fully compatible with CIC and did not respond to the maximum tolerable anticholinergic dose. It was observed that 6 weeks after BoNT-A treatment, 22 of the children (71%) became completely dry, 6 (19%) had improved leakage, and 3 (10%) had a partial improvement with occasional leaks. The mean maximal cystometric capacity increased from 152.90 ±76.97 mL (range, 45–324 mL) to 243.74±103.09 mL (range, 88–600 mL), the maximum detrusor pressure decreased from 57.1±29.44 cm H2O (range, 21–140 cm H2O) to 29.65±13.94 cm H2O (range, 11–61 cm H2O), and bladder compliance improved significantly from 3.77±3.14 mL/cm H2O to 11.26±7.33 mL/cm H2O (P<0.001, P<0.001, P<0.001, respectively). The urodynamic study results are summarized in Table 1. The grade of reflux was mild (grades 1, 2), intermediate (grade 3), and severe (grades 4, 5) in 25, 7, and 8 ureters, respectively. It was observed that reflux disappeared in 16 children (40%), improved in 17 children (42.5%), remained unchanged in 5 children (12.5%), and became worse in 2 children (5%) after BoNT-A treatment. Tables 2 and 3 show VUR status before and after BoNT-A treatment.

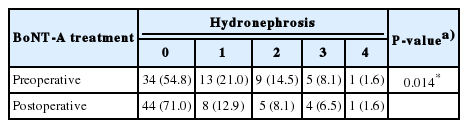

The hydronephrosis grade in ultrasound imaging before BoNT-A treatment was normal in 34 renal units (54.8%), mild (grades 1–2) in 22 (35.48%), moderate (grade 3) in 5 (8.1%), and severe (grade 4) in 1 (1.6%). Postoperative ultrasonography showed no hydronephrosis in 44 children (71.0%), mild hydronephrosis (grades 1–2) in 13 (21.0%), moderate hydronephrosis (grade 3) in 4 (6.5%), and worsened hydronephrosis (grade 4) in 1 (1.6%), respectively. Hydronephrosis was improved in 18 renal units (29.03%) at the follow-up. Tables 4 and 5 show the changes in hydronephrosis. No serious adverse events were observed.

DISCUSSION

Compared to primary VUR, secondary VUR in NB is unlikely to resolve spontaneously, and it is less likely to heal with antireflux surgery independent of the surgical method. This is due to suboptimal bladder dynamics. The key to improved results is to ensure adequate bladder capacity and compliance. In the past, urinary diversion was considered as the most ideal treatment for VUR in children with myelodysplasia, but the long-term results showed that this was not appropriate for these cases. In 1972, Lapides and Diocno introduced CIC as an adequate and safe method for drainage in cases of NB. Since then, CIC has become the mainstay treatment of NB. Anticholinergics and CIC are reliable methods for lowering intravesical pressure during bladder filling and emptying [14]. In 30%–50% of cases, VUR resolution can be achieved in 2–3 years with CIC and medical treatment [15,16]. The timing of CIC initiation depends on the physician, the presence of detrusor sphincter dyssynergia, the high potential of deterioration of the upper urinary tract, and the presence of high leak point pressures, but when started at a young age, the child and parent adapt more easily to CIC [2].

Ureteral reimplantation alone is a reasonable approach if there is adequate bladder capacity and compliance. Surgery is difficult in NB, and intravesical techniques in particular increase the risk of ureteral obstruction. The Cohen cross-trigonal technique approaches a 100% success rate for primary VUR, whereas its success in secondary VUR is only 85%–96% [17,18].

Although the success rate was higher for primary VUR, the success rate of endoscopic procedures for NB has been reported to range from 53% to 86% [6,19]. Recently, studies have shown the effectiveness of a combination of subureteral injections and BoNT-A to target elevated pressures and reflux [20].

Since the first use of BoNT-A (Botox) for NB, studies have shown that BoNT-A is a safe and effective second-line treatment of both idiopathic detrusor overactivity and cases of NB that are unresponsive to standard conservative treatment [21,22]. BoNT-A treatment has been found to yield excellent results in the pediatric population [10,23]. A significant improvement was observed in urodynamic parameters after BoNT-A treatment in our study, including a 59% increase in capacity and a 48% decrease in pressure. It was observed that the frequency of CIC, as well as the frequency of urine leakage, improved after BoNT-A treatment in our study, confirming previous findings [22,24]. Twenty-two children (71%) became completely dry, 6 children (19%) showed improved leakage, and 3 children (10%) had partial improvement with occasional leaks. Initially, we investigated whether BoNT-A solely exerted its effects by reducing intravesical pressure to resolve VUR. With this minimally invasive technique, 82.5% of refluxing ureters either disappeared or regressed. However, Neel et al. [20] suggested combining endoscopic treatment of VUR with BoNT-A injection to prevent recurrence of reflux, showing that BoNT-A treatment was effective for the regression of VUR in patients with myelomeningocele. Mascarenhas et al. [25] showed that BoNT-A injections did not cause de novo VUR despite trigonal injections. In fact, they showed that VUR regression could be obtained using BoNT-A injections. In our study, reflux worsened after BoNT-A injection in 2 children, but there was no clear reason for this deterioration. A higher dose of BoNT-A may have a different effect on the antireflux mechanism, but we did not have the opportunity to investigate this possibility. No serious adverse events were observed. We observed that hydronephrosis regressed in 64.2% of renal units. This finding can most likely be explained by the decrease in bladder pressure after BoNT-A treatment.

This study is retrospective and has a small sample size, but it also contains a large cohort of children treated for NB due to myelodysplasia. There were no data on videourodynamic studies in our study, although such information could yield better information regarding the relationship between increased bladder pressure and VUR. We did not have the opportunity to compare different doses of BoNT-A injections, which should be investigated in further studies.

In conclusion, in children with NB due to myelodysplasia, it is necessary to maintain bladder dynamics at reasonable levels to prevent VUR and to improve the success of other treatments. For this purpose, BoNT-A is an effective and safe second-line treatment option for patients with NB who are refractory to antimuscarinics. It is possible to enhance continence, reduce bladder pressure, and increase the maximum bladder capacity by using intradetrusor injections of BoNT-A. This minimally invasive treatment can protect the upper urinary tract from the possible effects of VUR and enhance the success rate of other treatment modalities. Although our results are promising, the risks and benefits of management options must be weighed with due consideration of each individual case, and long-term prospective studies with larger groups are warranted to investigate this method of treatment.

Notes

Research Ethics

The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Medeniyet University Goztepe Research and Training Hospital approval (approval number: 2019/0504). Written informed consent form has obtained from participants.

Conflict of Interest

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTION STATEMENT

·Full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis: TT, YOD, AV

·Study concept and design: TT, YOD, AV

·Acquisition of data: YOD, TT

·Analysis and interpretation of data: TT, YOD

·Drafting of the manuscript: TT, YOD

·Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: AV

·Statistical analysis: TT, YOD

·Obtained funding: None

·Administrative, technical, or material support: None

·Study supervision: AV