|

|

- Search

| Int Neurourol J > Volume 25(3); 2021 > Article |

|

ABSTRACT

Purpose

We aimed to develop urodynamic criteria to improve the accuracy of the diagnosis of bladder outlet obstruction (BOO) and detrusor underactivity (DU) in women with lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS).

Methods

Initially, in a group of 68 consecutive women with LUTS and increased postvoid residual (PVR) who had undergone urodynamic investigations, we examined the level of agreement between the operating physician‚Äôs diagnosis of BOO or DU and the diagnosis according to urodynamic nomograms/indices, including the Blaivas-Groutz (B-G) nomogram, urethral resistance factor (URA), bladder outlet obstruction index (BOOI), and bladder contractility index (BCI). Based on the initial results, we categorized 160 women into 4 groups using the B-G nomogram and URA (group 1, severe-moderate BOO; group 2, mild BOO and URA‚Č•20; group 3, mild BOO and URA<20; group 4, nonobstructed) and compared the urodynamic parameters. Finally, we redefined women as obstructed (groups 1+2) and nonobstructed (groups 3+4) for subanalysis.

Results

The agreement between the B-G nomogram and physician‚Äôs diagnosis was poor in the mild obstruction zone (őļ=0.308, P=0.01). By adding URA (cutoff value=20), excellent agreement was reached (őļ=0.856, P<0.001). Statistically significant differences were found among the 4 groups (analysis of variance) in maximum flow rate (Qmax) (P<0.0001), voided volume (VV) (P=0.042), PVR (P=0.032), BOOI (P<0.0001), and BCI (P<0.0001), with a positive linear trend for Qmax and VV and a negative linear trend for PVR and BOOI moving from groups 1 to 4. In the subanalysis, all parameters showed statistically significant differences between obstructed and nonobstructed women, except BCI (Qmax, P=0.0001; VV, P=0.0091; PVR, P=0.0005; BOOI, P=0.0001).

Although urodynamic bladder outlet obstruction (BOO) is adequately defined in men with lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS), there is still no definitive urodynamic definition of female BOO in the most recent documents of the International Continence Society (ICS) and the International Urogynecological Association [1]. It is also well known that a proportion of women may urinate ‚Äúnormally‚ÄĚ without any detrusor contraction, but only via pelvic floor muscle relaxation. Furthermore, the definition of detrusor underactivity (DU) is under reconsideration for both males and females [2].

Bladder emptying involves a constant interaction between detrusor contraction (isometric and isotonic) and outflow resistance (active and passive). Thus, in both sexes, abnormal postvoid residual (PVR) should be considered to be due to detrusor insufficiency only when BOO has been excluded [3]. Without an accurate definition of female BOO, it remains difficult to define female DU, and the urodynamic diagnosis of obstruction or underactivity is therefore subjective and physiciandependent, especially in equivocal cases.

This study aimed to develop criteria to improve the accuracy of the diagnosis of BOO and DU in women with LUTS, by combining nomograms and indices that are currently applied for the diagnosis of BOO and DU in men and women.

The study was performed according to the Helsinki Declaration and approved by the Research Ethics Committee of our University (Nr. 447/18-7-2018). It was conducted in 2 phases. The first phase included 68 consecutive women who had undergone a pressure-flow study primarily due to voiding symptoms and at least moderate PVR (‚Č•100 mL) after 2 uroflowmetric recordings. We retrospectively evaluated the agreement of the urodynamic clinical diagnoses made by 3 independent functional urologists concerning BOO and DU with the generally accepted urodynamic nonograms and indices for defining BOO and DU, which are mostly used in men, but also in women. The relevant indices are defined below:

¬∑Bladder outlet obstruction index (BOOI): BOOI=detrusor pressure at Qmax [PdetQmax] ‚Äď maximum flow rate [Qmax]

·Urethral resistance factor (URA) [4]:

·The Blaivas-Groutz (B-G) nomogram.

All nomograms and indices were calculated from the pressureflow study results. We investigated the correlation of the physicians‚Äô diagnosis of obstruction, which was based on the ICS definitions of BOO/DU, normal urodynamic pressures, and the urodynamic traces, with the B-G nomogram and the following index values: URA‚Č•20, BOOI‚Č•40, and BCI‚Č•100. In order to evaluate the agreement between the diagnosis and the nomograms or indices, the őļ coefficient was used.

In the second phase of the study, we retrospectively assessed urodynamic data from 160 women with refractory LUTS. Using the results from the initial phase, the women were categorized into 4 groups according to the B-G nomogram and URA. Group 1 included women with severe or moderate obstruction according to the B-G nomogram, group 2 comprised women with mild obstruction (B-G nomogram) and URA‚Č•20, group 3 was composed of women with mild obstruction (B-G nomogram) and URA<20, and group 4 consisted of unobstructed women (B-G nomogram). The adequacy of the URA threshold value (‚Č•20) for the purposes of this study was tested with binary logistic regression analysis. The voided volume (VV), maximum flow rate (Qmax), and PVR from pressure-flow studies, as well as the BOOI and BCI, were compared between the groups using non-parametric tests, as the Shapiro-Wilk test showed that the assumption of normality was violated in most cases. Binary logistic regression analyses with backward conditional elimination of nonsignificant parameters were used to further investigate differences between the groups. In addition, we used canonical discriminant analysis for the explanatory variables to refine the definitions of the 4 groups. Subsequently, we redefined women as conventionally obstructed (groups 1+2) and nonobstructed (groups 3+4), and we conducted binary logistic regression and receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analyses with the new groups. The threshold of statistical significance was set at P<0.05 for type I error. As a final step, we distributed the proportion of women with incomplete bladder emptying (bladder voiding efficiency [BVE] <80%; defined as BVE=VV/(VV+PVR) √ó100%) in each of those 4 groups, in order to identify the distribution of BOO and DU in patients with bladder-emptying dysfunction.

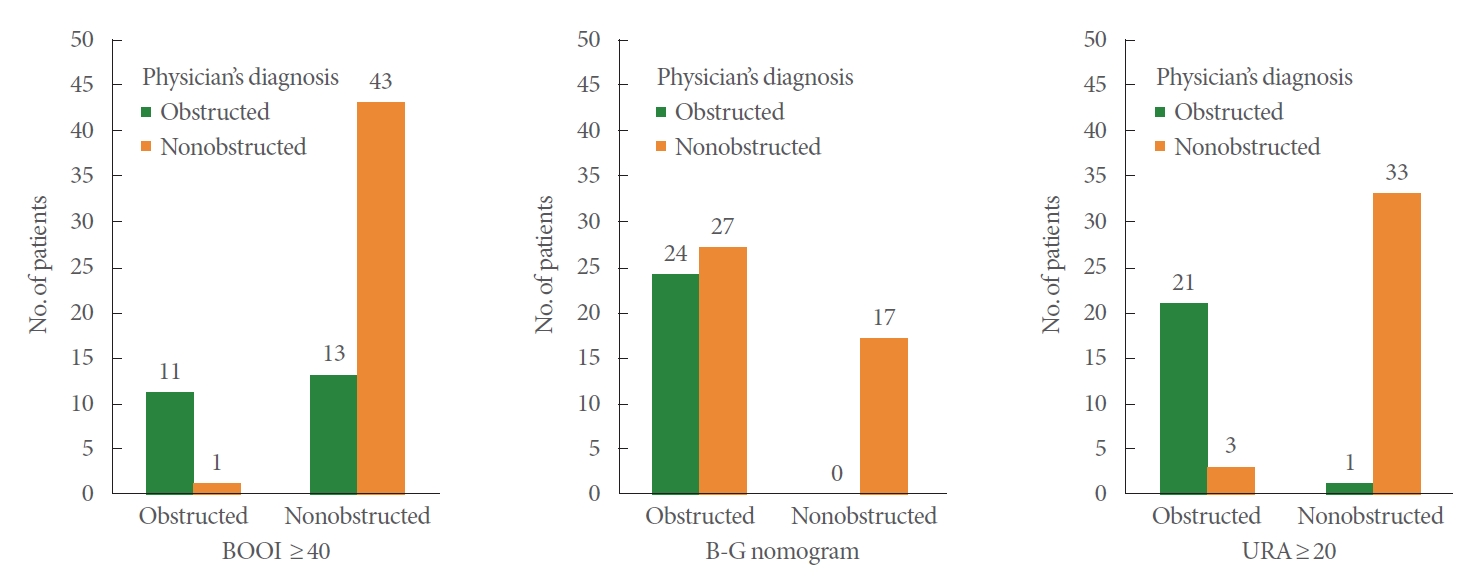

In the preliminary phase of the study, the results of urodynamic pressure-flow studies of 68 consecutive women with voiding dysfunction and a mean age of 61.5 years (range, 18‚Äď82 years) were analyzed. The physicians‚Äô diagnosis based on the urodynamic traces and parameter values of these women was ‚Äúobstructed‚ÄĚ in 24 (35%), ‚Äúunderactive‚ÄĚ in 40 (59%), and ‚Äúnormal‚ÄĚ in 4 (6%). Women with a clinician‚Äôs diagnosis of DU were older than those diagnosed as obstructed (61.9¬Ī17.8 years vs. 49.0¬Ī13.4 years, P=0.005). The clinician‚Äôs diagnosis of obstructed voiding was consistent with a BOOI‚Č•40 in 79.4% of cases, but the statistical level of agreement was moderate (őļ coefficient, after chance was excluded=0.491; P=0.01). Furthermore, the clinician‚Äôs diagnosis of obstruction coincided with a BOO diagnosis by the B-G nomogram in 60.3% of cases, but with a low level of statistical agreement (őļ=0.308, P=0.01). In a subanalysis of the zones of obstruction in the B-G nomogram, an excellent level of agreement was reached (almost 100%) in the zones of severe and moderate obstruction, but in the zone of mild obstruction, most women were diagnosed as underactive (26 of 34, 76.5%) rather than obstructed (8 of 34, 23.5%). In contrast, when using the parameter URA‚Č•20, an excellent level of agreement with the physician‚Äôs diagnosis of obstruction was noted (93%, őļ=0.856, P<0.001) (Fig. 1). Finally, agreement was not found between the physician‚Äôs diagnosis of underactivity and BCI<100 (őļ=0.190, P=0.386).

The descriptive statistics of the mean age and urodynamic pressure-flow parameters of the 4 groups of women with voiding dysfunction are given in Table 1.

We first compared the mean values of urodynamic parameters (URA, PdetQmax, BOOI, BCI) and free-flow parameters (free Qmax, free VV, and free PVR) between patients who were clearly obstructed (group 1) and those who were nonobstructed (group 4). All parameters, except for the mean BCI values (P=0.880), differed significantly between the 2 groups (all P<0.05). We also tested which variables more accurately predicted group categorization when all the variables were used in the same model simultaneously. Free Qmax, free VV, and BOOI were the variables included as significant in the final model (P<0.05). The model predicted categorization correctly in 100% of cases.

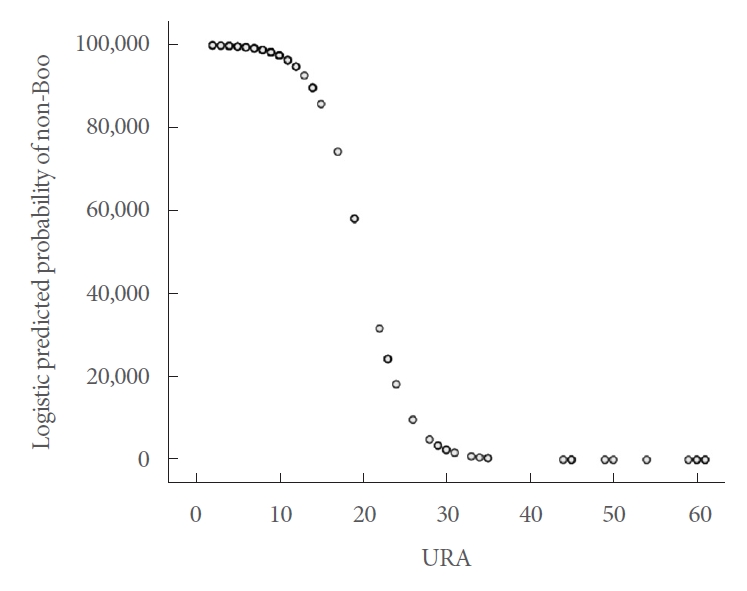

Since URA differed significantly between groups 1 and 4 (and among all groups in the analyses that follow), we tested the research hypothesis that URA could be used to further classify patients. To explore this hypothesis, and thus to find the optimal threshold of URA, we used binary logistic regression on groups 1 and 4. The model predicted 94.5% of the cases correctly, with an estimated coefficient of URA that was highly statistically significant (P<0.01). A scatter-plot of the estimated probabilities and URA (Fig. 2) shows that the optimal cutoff point (corresponding to an estimated probability of non-BOO equal to 0.5) was 20. Thus, we used the threshold of URA=20 to further categorize patients with mild obstruction in the B-G nomogram into 2 subgroups: mild B-G obstruction and URA‚Č•20 (group 2) and mild B-G obstruction and URA<20 (group 3).

The mean values of the parameters free Qmax, free VV, and free PVR did not differ significantly between the 2 groups (P>0.05), but there were significant differences in URA, PdetQmax, BCI, and BOOI (all P<0.01). In addition, following the approach used to compare groups 1 and 4, we tested a model that predicted categorization when groups 1 and 2 were compared. The only explanatory variable that was significant was PdetQmax (P<0.01). Although this model could predict the correct grouping for only 68.2% of patients, it seems that PdetQmax is a sensitive parameter that can differentiate between groups that are similar to each other. It should be noted that, according to the research questions, groups 1 and 2 were quite similar. That is, the less significant the predictors were in this particular model, the higher the similarity was between groups 1 and 2. These results provide evidence that groups 1 and 2 were quite similar, with the exception of the significant variable PdetQmax mentioned above.

We then tested whether groups 3 and 4 differed significantly according to various parameters. The mean values of free VV and BCI did not differ significantly (Mann-Whitney test, P>0.05), but there were significant differences in free Qmax, free PVR, URA, PdetQmax, and BOOI (P<0.05). When further exploring the hypothesis that groups 3 and 4 did not differ significantly, free VV, free PVR and PdetQmax were significant predictors (P<0.01) in a model predicting the categorization of 78.4% of patients correctly. The results of the comparisons between groups 1 and 2 and between groups 3 and 4 suggest that group 2 was more similar to group 1 than group 3 was to group 4.

The hypothesis that groups 2 and 3 differed significantly was tested; 5 out of 7 comparisons showed significant differences (Free Qmax, URA, PdetQmax, BCI, and BOOI, all P<0.05). In contrast, the mean values of free VV and free PVR did not differ significantly. We further examined whether the same pattern of significant predictors that was found in the comparison of groups 1 and 4 was repeated for the comparison of groups 2 and 3. The only significant predictor in the final model was BOOI (P<0.01) and the model predicted the categorization of 90.9% of patients correctly. This result provides further evidence that BOOI can significantly predict group categorization, since the same finding resulted from the comparison of groups 1 and 4. The parameters of free uroflowmetry that were significant in the model that compared groups 1 and 4 did not provide a clear classification between groups 2 and 3. To graphically summarize the results of all pairwise comparisons of the groups, we conducted canonical discriminant analysis for all the predictors used in the logistic regression models (Fig. 3). The analysis confirmed the above findings.

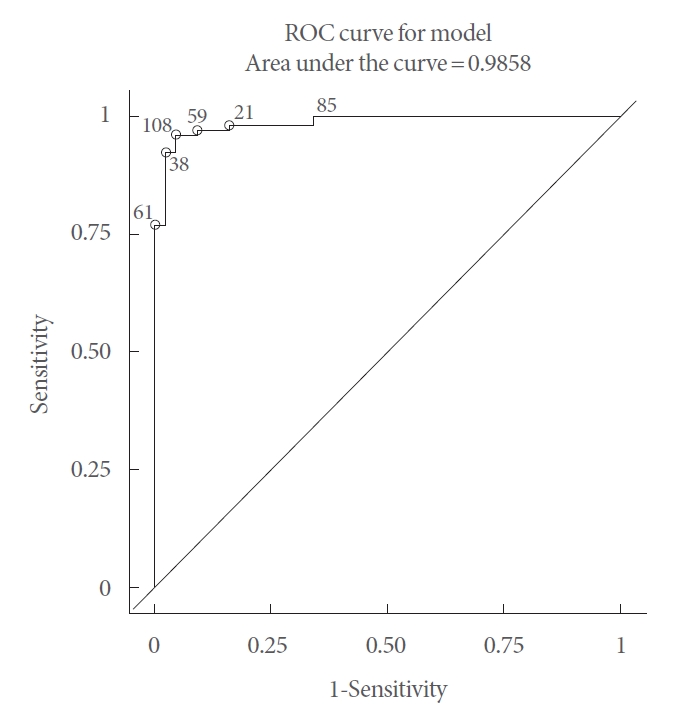

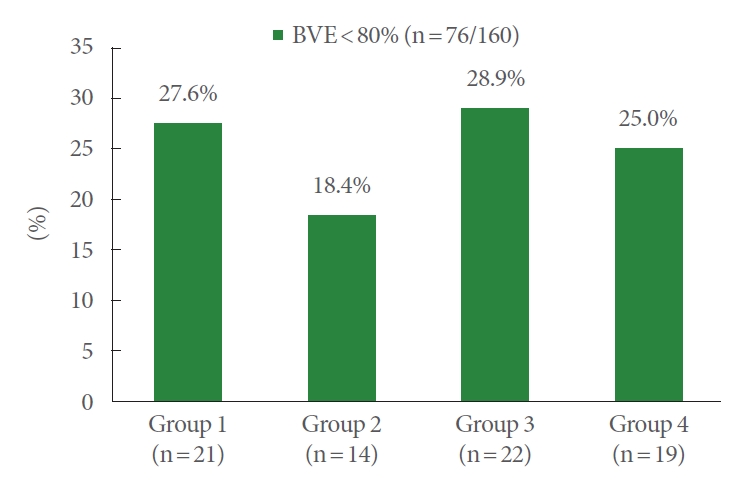

Given the results above (regarding the similarities and dissimilarities of groups), the next step in the analysis was to examine whether merging groups 1 and 2 together, and groups 3 and 4 together, would provide a statistical model with acceptable fit. The final model showed that the significant parameters were free Qmax, free VV, PdetQmax, and BOOI (P<0.05), and it accurately predicted the grouping of 95.9% of patients. The model is quite similar to the model that was found from the comparison of groups 1 and 4 in the previous analysis, with the addition of PdetQmax, which was found to be a significant predictor in cases of small dissimilarities. Moreover, the area under the ROC curve of the model given in Fig. 4 is 0.9858. Thus, the model can adequately discriminate the patients into 1 of these 2 groups. Finally, in the women with incomplete bladder emptying during uroflowmetry (47.5%, 76 of 160), DU rather than BOO seemed to be the primary cause of voiding dysfunction in almost half of the cases (groups C and D: 53.9% [41 of 76]), as shown in Fig. 5.

The results from our cohort of women with refractory LUTS suggest that the combination of the parameter URA>20 with the B-G nomogram may increase the diagnostic accuracy of BOO in women (female BOO, f-BOO). Despite the large number of helpful urodynamic nomograms and indices for diagnosing BOO in men, only limited data exist for defining f-BOO. Consequently, there is not yet an established definition of obstruction, using urodynamic criteria, in women with voiding symptoms (reduced flow, hesitancy, sensation of incomplete bladder emptying, voiding difficulty) [5]. The B-G nomogram is probably the simplest and most widely used tool for defining f-BOO today. However, it has received substantial criticism for its specificity [6,7]. Furthermore, there are limited published data concerning the diagnostic value of URA in f-BOO. Kranse and van Mastrigt proposed the term ‚Äúrelative obstruction‚ÄĚ both for males and females, using the urodynamic parameter URA/w20 (the ratio of the obstruction parameter URA to the Watts factor [a bladder contractility parameter] at 20% [w20]) [8]. According to M√©ndez-Rubio et al. [8], videourodynamic evaluations of 88 women with significant PVR showed a positive linear correlation between PVR and URA, as well as between PVR and abdominal straining during micturition. Moreover, there is a limited number of studies using the combination of PdetQmax and Qmax from pressure-flow studies in order to define f-BOO, and with different proposed cutoff values [5,10]. In a prospective study, the sensitivity and specificity of the combination of Qmax<15 mL/sec and PdetQmax>20 cm H2O for diagnosing f-BOO were 74.3% and 91.1%, respectively [11].

Women with voiding difficulty represent a heterogeneous population. According to Gomes et al. [12], elderly patients with LUTS suggestive of obstruction frequently do not have underlying BOO pathophysiology. Lowenstein et al [13]. reached the same conclusion in a more recent study. In our study, only 49 out of the 160 women (30.6%) with refractory LUTS were diagnosed as obstructed. This result also agrees with the study of Nitti et al. [14], in which only 29% (n=76) of women with nonneurogenic voiding dysfunction were diagnosed with f-BOO using videourodynamic studies, while the remaining 71% (n=184) were not considered obstructed.

In another videourodynamic study evaluating 52 women with dysfunctional voiding, the specificity of the B-G nomogram in diagnosing f-BOO was found to be 67.5%. The major diagnostic discrepancy was observed in the mild obstruction zone of the B-G nomogram, with only one-third of these women diagnosed with obstruction during the videourodynamic study [7]. We observed similar results in both phases of our study, as only 25% (17 of 68) of women in the mild obstruction zone of the B-G nomogram were diagnosed with f-BOO using the URA‚Č•20 parameter. Other researchers also concluded that the B-G nomogram may overestimate f-BOO, and they do not recommend using it without a second distinct urodynamic parameter or index [6,15]. Furthermore, according to our results, women within the severe or moderate obstruction zones of the B-G nomogram could be safely and accurately diagnosed with obstruction. The mild obstruction zone seems to be the gray area or equivocal zone of obstruction in women. Aganovińá proposed using URA with a cutoff value of 29 in order to diagnose clear BOO among men with equivocal obstruction [16]. We respectively propose using URA with a cutoff value of 20 to diagnose clear BOO in women with equivocal (mild) obstruction.

The contribution of DU to incomplete bladder emptying seems to be underestimated by the B-G nomogram [3]. Our results suggest that women with mild obstruction are relatively underactive compared to both women without f-BOO and women with clear f-BOO. We estimated that DU contributed to incomplete bladder emptying in 61.1% of these women (22 of 36) (Fig. 5). The efficiency of detrusor contraction to empty the bladder is highly understudied in women, and there is no generally accepted urodynamic parameter or index to distinguish between normal and underactive bladder. According to Cucchi et al. [17], an isolated decrease in the duration of detrusor contraction (fading contraction) constitutes the preliminary phase of DU in women with significant PVR. Moreover, this seems to be a pathological process, rather than a normal change due to aging. In a study by Salinas et al. [18], isotonic DU (W80‚ÄďW20<0) in women was found to be statistically correlated with incomplete bladder emptying. This correlation was more obvious in women with high-grade cystocele. However, Wmax was not found to be useful as an index of detrusor contractility in women [19]. Furthermore, Valentini et al. [20] found that, with increasing age, in women with LUTS, there was a decrease of detrusor pressure at the initiation of voiding, PdetQmax, and Qmax, while PVR increased significantly in women older than 75 years.

Current urodynamic nomograms and indices do not take into account parameters such as the duration of detrusor contraction and BVE, which are used in the definition of DU according to the ICS. Furthermore, urodynamic software cannot efficiently identify factors such as abdominal straining during voiding or the voiding pattern, which significantly affect the results of nomograms or indices. Women with purely abdominal micturition and with no detrusor contraction during micturition were excluded from our study. Thus, the operating physician plays a vitally important role in the evaluation of the urodynamic study results to reach a diagnosis. In order to bypass the subjectivity of a single physician’s diagnosis in the preliminary phase of our study, we included diagnoses from 3 independent functional urologists.

There are certain limitations of our study. This was a singlecenter, retrospective study, and the results should be validated in larger, multicenter, prospective studies, using a control group of healthy women without urinary symptoms. Another possible caveat to our study is the lack of videourodynamic evaluations, which could provide additional information on the pathophysiology of f-BOO in those women. However, a videourodynamic evaluation of 207 women with symptoms suggestive of f-BOO identified anatomic causes of f-BOO in only 13.1% of them (high-grade pelvic organ prolapse in 6.3% and urethral stricture in 6.8%) [10].

In conclusion, the results of this study suggest that the combination of URA with the B-G nomogram may increase the diagnostic accuracy of BOO in women. Based on our results, the mild obstruction zone of the B-G nomogram represents a heterogeneous population of women, with at least half of them being rather underactive than obstructed. We propose the use of URA‚Č•20 as a cutoff value in this group of patients in order to increase the diagnostic accuracy of f-BOO and indirectly improve the diagnosis of female DU, especially in women with incomplete bladder emptying and no evidence of increased outlet resistance.

NOTES

Grant/Funding Support

Astellas Pharma Inc., provided an unrestricted educational grant that made possible the statistical analysis of the results of this study.

Research Ethics

The study was performed according to the Helsinki Declaration and was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Aristotle University of Thessaloniki (Nr. 447/18-7-2018).

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTION STATEMENT

·Conceptualization: KM, AA

·Data curation: KM, AO, IS, MK, GM, EN

·Formal analysis: IS, MK, GM

·Funding acquisition: AA

·Methodology: KM, AO, IS, GM, EN

·Project administration: AA

·Visualization: AA

·Writing-original draft: KM, AO, IS, MK, EN, AA

·Writing-review & editing: KM, IS, GM, AA

REFERENCES

1. Haylen BT, De Ridder D, Freeman RM, Swift SE, Berghmans B, Lee J, et al. An International Urogynecological Association (IUGA)/International Continence Society (ICS) joint report on the terminology for female pelvic floor dysfunction. Neurourol Urody 2010;29:4-20.

2. Osman NI, Chapple CR, Abrams P, Dmochowski R, Haab F, Nitti V, et al. Detrusor underactivity and the underactive bladder: a new clinical entity? A review of current terminology, definitions, epidemiology, aetiology, and diagnosis. Eur Urol 2014;65:389-98. PMID: 24184024

3. Hoag N, Gani J. Underactive bladder: clinical features, urodynamic parameters, and treatment. Int Neurourol J 2015;19:185-9. PMID: 26620901

4. Sekido N. Bladder contractility and urethral resistance relation: what does a pressure flow study tell us? Int J Urol 2012;19:216-28. PMID: 22233177

5. Groutz A, Blaivas JG. Non-neurogenic female voiding dysfunction. Curr Opin Urol 2002;12:311-6. PMID: 12072652

6. Akikwala TV, Fleischman N, Nitti VW. Comparison of diagnostic criteria for female bladder outlet obstruction. J Urol 2006;176:2093-7. PMID: 17070266

7. Vírseda CM, Salinas CJ, Adot ZJ, Martín GC. May the Blaivas and Groutz nomogram substitute videourodynamic studies in the diagnosis of female lower urinary tract obstruction? Arch Esp Urol 2006;59:601-6 (Spanish). PMID: 16933488

9. Méndez-Rubio S, Chiarelli L, Salinas-Casado J, Cano S, VirsedaChamorro M, Ramírez J, et al. Postmicturition residual; urodynamic. Actas Urol Esp 2010;34:365-71. PMID: 20470699

10. Kuo HC. Videourodynamic characteristics and lower urinary tract symptoms of female bladder outlet obstruction. Urology 2005;66:1005-9. PMID: 16286113

11. Chassagne S, Bernier PA, Haab F, Roehrborn CG, Reisch JS, Zimmern PE. Proposed cutoff values to define bladder outlet obstruction in women. Urology 1998;51:408-11. PMID: 9510344

12. Gomes CM, Arap S, Trigo-Rocha FE. Voiding dysfunction and urodynamic abnormalities in elderly patients. Rev Hosp Clin Fac Med Sao Paulo 2004;59:206-15. PMID: 15361987

13. Lowenstein L, Anderson C, Kenton K, Dooley Y, Brubaker L. Obstructive voiding symptoms are not predictive of elevated postvoid residual urine volumes. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct 2008;19:801-4. PMID: 18074067

14. Nitti VW, Tu LM, Gitlin J. Diagnosing bladder outlet obstruction in women. J Urol 1999;161:1535-40. PMID: 10210391

15. Lee YS, Lee KS, Choo MS, Kim JC, Lee JG, Seo JT, et al. Efficacy of an alpha-blocker for the treatment of nonneurogenic voiding dysfunction in women: an 8-week, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Int Neurourol J 2018;22:30-40. PMID: 29609420

16. Aganovińá D. The urodynamic nomogram in defining the degree of obstruction in patients with benign prostatic enlargement--defining clear obstruction. Med Arh 2003;57:81-6.

17. Cucchi A, Quaglini S, Rovereto B. Development of idiopathic detrusor underactivity in women: from isolated decrease in contraction velocity to obvious impairment of voiding function. Urology 2008;71:844-8. PMID: 18455627

18. Salinas JC, Adot JZ, Dambros M, Vírseda MC, Ramírez JF, Moreno JS, et al. Factors for voiding dysfunction and cystocele. Arch Esp Urol 2005;58:316-23 (Spanish). PMID: 15989095

19. Vírseda CM, Teba DPF, Salinas CJ, Fernández LC, Arredondo MF. Pressure-flow studies in the diagnosis of micturition disorders in the female. Arch Esp Urol 1998;51:1021-8 (Spanish). PMID: 9951125

20. Valentini FA, Robain G, Marti BG. Urodynamics in women from menopause to oldest age: what motive? What diagnosis? Int Braz J Urol 2011;37:100-7. PMID: 21385486

Fig. 1.

Agreement between the final physician‚Äôs diagnosis and urodynamic parameters under evaluation. The use of URA ‚Č•20 as a cutoff value provided the highest level of agreement with the physician‚Äôs diagnosis of obstruction. BOOI, bladder outlet obstruction index; URA, urethral resistance factor.

Fig. 2.

Estimated probabilities of non-BOO versus URA values, based on the logistic regression model. The optimal cutoff point for URA was calculated to be 20. BOO, bladder outlet obstruction; URA, urethral resistance factor.

Fig. 3.

Canonical discriminant analysis graph of patients‚Äô group categorization. Group 2 (red) is closer to the definitive obstruction group 1 (blue) than group 3 (green) is to the definitive nonobstruction group 4. Group 1, severe-moderate BOO; group 2, mild BOO and URA‚Č•20; group 3, mild BOO and URA<20; group 4, nonobstructed. BOO, bladder outlet obstruction; URA, urethral resistance factor.

Fig. 4.

Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve of the binary logistic regression model for the 2 merged groups.

Fig. 5.

Incomplete bladder emptying during free urinary flow, distributed across the 4 groups of patients. In almost half of the patients, the primary cause seemed to be detrusor underactivity rather than obstruction. Group 1, severe-moderate BOO; group 2, mild BOO and URA‚Č•20; group 3, mild BOO and URA<20; group 4, nonobstructed. BOO, bladder outlet obstruction; URA, urethral resistance factor; BVE, bladder voiding efficiency

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics of the urodynamic parameters and indices investigated during the study, with categorization per patient group

Values are presented as mean¬Īstandard deviation.

Group 1, severe-moderate bladder outlet obstruction (BOO); group 2, mild BOO and URA‚Č•20; group 3, mild BOO and URA<20; group 4, nonobstructed; Qmax, maximum flow rate; VV, voided volume; PVR, postvoid residual; PdetQmax, detrusor pressure at Qmax; URA, urethral resistance factor; BOOI, bladder outlet obstruction index; BCI, bladder contractility index.