Duration of Antimuscarinic Administration for Treatment of Overactive Bladder Before Which One Can Assess Efficacy: An Analysis of Predictive Factors

Article information

Abstract

Purpose:

To determine the duration of antimuscarinic therapy for overactive bladder syndrome (OAB) appropriate for assessment of the efficacy of treatment, and to evaluate the possible predictive factors for response to therapy.

Methods:

All OAB patients who visited a urology outpatient clinic of a tertiary referral center and who were prescribed 5 mg of solifenacin or 4 mg of tolterodine extended release capsules daily were enrolled in the study. Patients were asked to continue therapy for 6 months. All enrolled patients completed the patient perception of bladder condition, overactive bladder symptom score (OABSS), and the modified Indevus Urgency Severity Scale questionnaires. All patients underwent uroflowmetry.

Results:

A total of 164 patients were enrolled and 125 patients (76%) had at least one follow-up visit. The mean follow-up interval was 1 month (range, 0.5–6 months). Sixty-two patients (49.6%; 95% confidence interval [CI], 40.7–58.5) responded to antimuscarinic treatment. The median time for the onset of response was 3 months (95% CI, 1–6). Multivariate Cox proportional-hazards model revealed that elevated baseline OABSS was an independent predictor of responsiveness to therapy. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis revealed an optimal OABSS cutoff value of ≥7, with an area under the ROC curve of 0.79 (95% CI, 0.70–0.88; sensitivity, 91.9%; specificity, 60.7%).

Conclusions:

The median time for a therapeutic response was 3 months, and OABSS was the only predictor for responsiveness. These findings may serve as a guideline when prescribing antimuscarinic treatment for OAB patients.

INTRODUCTION

Overactive bladder syndrome (OAB), with or without incontinence, is characterized by urinary urgency, frequent urination, and nocturia. Muscarinic receptor antagonists are the first-line pharmacotherapeutic agents for the treatment of OAB. At present, several antimuscarinic drugs are available for the treatment of OAB. Each of these has demonstrated significant efficacy for the treatment of OAB symptoms, although their pharmacokinetic and adverse effect profiles vary [1,2].

The duration of antimuscarinic treatment for OAB has varied in previous studies, and there is no consensus regarding the optimal duration of treatment for OAB patients. The treatment durations in clinical studies have been reported to range from 2 weeks to 12 months [3-11], or as the time taken to reach an optimal dose (i.e., the dose that achieved a maximum dose or a balance between improvement in incontinence symptoms and tolerability of side effects) plus one additional week [12]. Nevertheless, a specific definition of refractory OAB would be useful, and would allow for timely initiation and evaluation of second-and third-line treatments [13].

In-depth knowledge about both the optimal duration of therapy and the predictors of response to antimuscarinic treatment would be helpful in clinical practice. Identification of patients likely to be refractory to antimuscarinic treatment could help prevent administration of ineffective medication and potential drug-related adverse effects. Thus, the aim of this study was to estimate the duration of treatment required before classifying a patient unresponsive to antimuscarinic therapy, and to determine if any factors predict a patient’s response to antimuscarinic treatment.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

One hundred sixty-four consecutive patients, who visited the urologic outpatient clinics of a referral hospital for treatment of OAB, were prospectively enrolled in this study. Inclusion criteria included age ≥18 years and ≥1-month history of OAB symptoms, including frequent and urgent urination, with or without incontinence. Patients with predominant symptoms of urinary stress incontinence, previous bladder or urethral surgery, possible neurogenic lesions, or active urinary tract infection were excluded. The study was approved by the Research Ethics Committees of Buddhist Tzu Chi General Hospital.

The screening visit was designated as visit 0. Eligibility was determined at visit 1 (baseline; 2 weeks after visit 0) using the results recorded in the 3-day voiding diary prior to visit 1. Differentiation between OAB-wet (i.e., at least one episode of urge urinary incontinence every 3 days) and OAB-dry (i.e., urgency at least once per day without urge urinary incontinence) was based on the presenting symptoms and the 3-day voiding diary. Patients received 5-mg solifenacin or 4-mg tolterodine extended-release (ER) capsules daily. Patients were followed-up at 2 weeks (visit 2), 1 month (visit 3), 3 months (visit 4), and 6 months (visit 5). In addition, patients who had received at least one dose of the study medication were evaluated for adverse events at each visit.

All enrolled patients were asked to complete the patient perception of bladder condition (PPBC) [14], the overactive bladder symptom score (OABSS) [15], the modified Indevus urgency severity scale (IUSS) [16], and the International Prostate Symptoms Score (IPSS) questionnaires [17]. The urgency severity scale was rated by marking 0, 1, 2, or 3, which were defined as none, mild, moderate, and severe urgency, respectively. In addition, urgency with urinary incontinence was assigned a score of 4 [18]. Total prostate volume and transition zone index were obtained by ultrasound in each patient. Uroflowmetry was performed and postvoid residual volume was measured by transabdominal ultrasound at each outpatient clinic visit. The voided volume was derived from the uroflowmetry data.

A response to antimuscarinic therapy was defined as a reduction of ≥3 in the OABSS from baseline until the follow-up visit [19]. Data of patients with at least one follow-up visit, who failed to attend further follow-ups before the occurrence of a response to antimuscarinic therapy, were considered censored data.

STATA 11.0 (StataCorp LP., College Station, TX, USA) was used for the statistical analysis. A Cox proportional-hazards model was applied to identify the factors affecting responsiveness. Multivariate analysis was performed using the criteria that univariate test of any variable had a P-value <0.05. A P-value <0.05 was considered statistically significant. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis was performed to identify the optimal cutoff value for predicting responsiveness. The optimal cutoff value was determined by the point on the ROC curve closest to the upper left-hand corner.

RESULTS

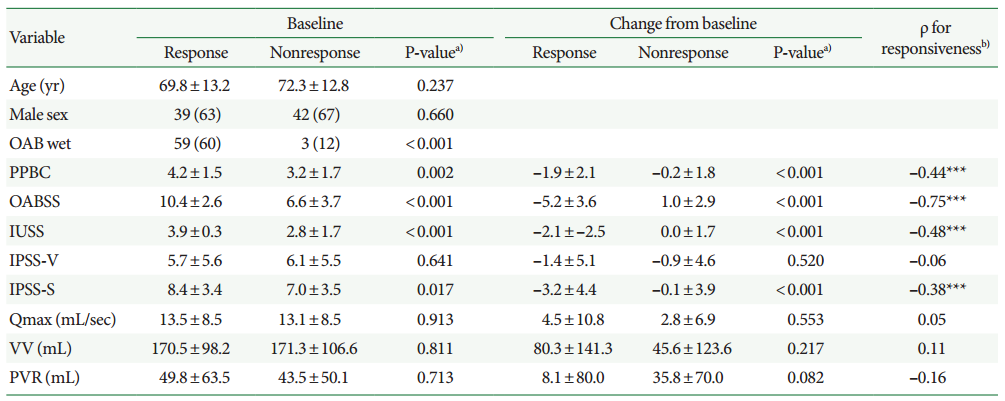

A total of 164 patients were enrolled in the study, among which 125 patients (76%) had at least one follow-up visit. Baseline data of these 125 patients, along-with follow-up visit data, are tabulated in Table 1. Except for age and maximum flow rate, the values of the other variables did not differ between women and men (Table 1). The mean follow-up interval was 1 month (range, 0.5–6 months). Sixty-two patients (49.6%; 95% confidence interval [CI], 40.7–58.5) were responsive to antimuscarinic therapy during the treatment period. The response rate did not differ between genders (Table 1). The median treatment duration before response was 3 months (95% CI, 1–6) (Fig. 1A). The nonresponsiveness probability curve did not differ between genders (P=0.423; log-rank test) (Fig. 1B). The persistence rate of antimuscarinics at 3 months was 40.8% (51 of 125).

Baseline characteristics of patients with overactive bladder syndrome, and their response rate and adverse effects

Probability of nonresponsiveness in all patients (A) and both genders (B) with overactive bladder syndrome undergoing antimuscarinic therapy over time.

Among the 62 responsive patients, 13 became unresponsive during follow-up. However, none of the baseline variables could predict this phenomenon.

In addition to antimuscarinics, 59 out of the 81 patients with benign prostate hyperplasia were concomitantly treated with an alpha blocker (tamsulosin [n=46], silodosin [n=8] or doxazosin [n=5]). Among these 59 patients, 12 patients also received 5-alpha reductase inhibitor treatment (dutasteride; Table 1).

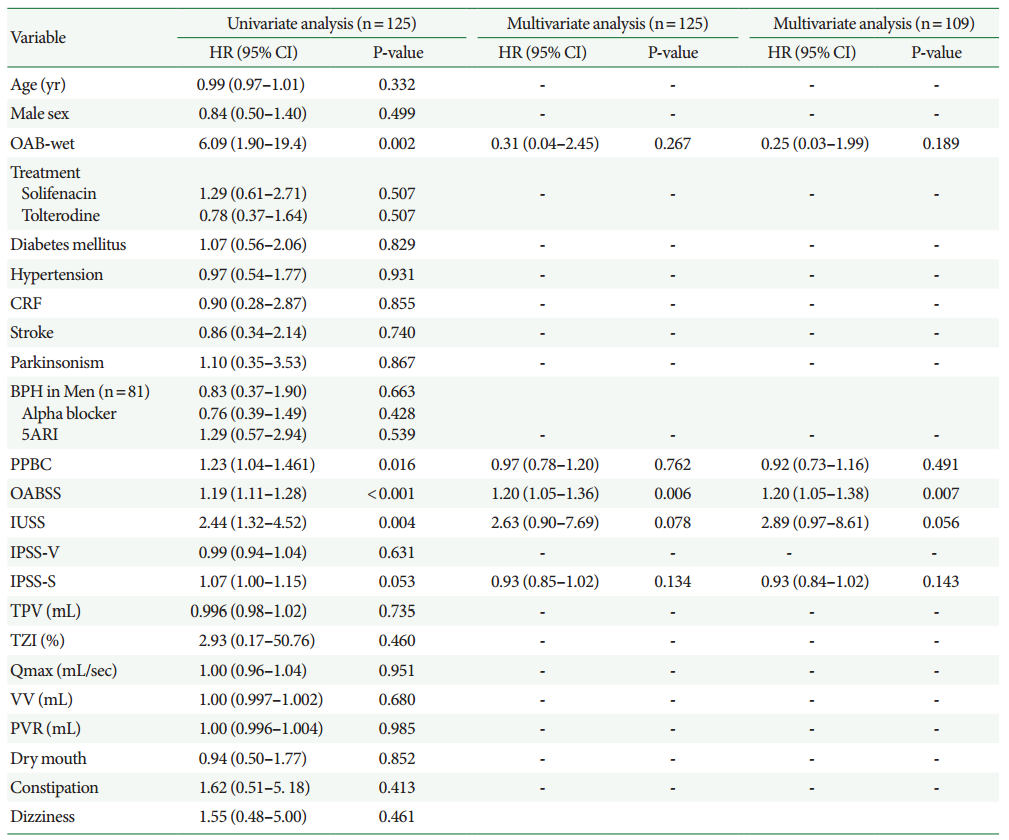

Univariate Cox proportional-hazards model revealed that the presence of OAB-wet and elevated baseline PPBC, OABSS, and IUSS were the factors associated with a response to therapy. However, multivariate Cox proportional-hazards model revealed that only a higher OABSS independently predicted a response to therapy (Table 2).

Cox proportional-hazards model for predicting responsiveness to antimuscarinic treatment for all patients (n=125) or patients excluding Parkinsonism and stroke (n=109)

ROC analysis revealed that an OABSS≥7 was the optimal cutoff value for predicting a response to therapy, with the area under the ROC curve being 0.79 (95% CI, 0.70–0.88; sensitivity, 91.9%; specificity, 60.7%) (Fig. 2).

Area under the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve for overactive bladder symptoms score as a predictive test for a response to antimuscarinic therapy.

Excluding all 16 patients with parkinsonism or stroke during the final analyses, OABSS remained the only independent predictor for a response to therapy (n=109; Table 2). ROC analysis also revealed that an OABSS≥7 was the optimal cutoff value for predicting a response to therapy, with the area under the ROC curve being 0.80 (95% CI, 0.71–0.89; sensitivity, 90.7%; specificity, 63.3%).

As compared with PPBC, IUSS, or IPSS storage subscore (IPSS-S). OABSS had the highest Spearman’s ρ between the responsiveness and the change of clinical data at last visit from baseline (Table 3).

DISCUSSION

We demonstrated that the average treatment duration of 3 months was necessary to determine the responsiveness to antimuscarinic therapy. To our knowledge, no previous studies have determined a minimum duration of treatment for assessing the responsiveness of OAB patients to antimuscarinic therapy. Additionally, there has been no universal definition of a response to antimuscarinics. Patients not responding after 3 or 6 months of antimuscarinic therapy have been labeled as refractory in some studies [20-22]. However, Brubaker et al. [23] defined refractory as inadequate symptom control after 2 or more attempts at pharmacotherapy. Nitti et al. [13] emphasized the importance of defining refractory OAB. A specific definition of refractory OAB would allow for proper initiation and evaluation of second- and third-line treatments. As is evident from Fig. 1, the probability of becoming responsive to therapy after 3 months was limited. Thus, based on our results, refractory OAB could be defined as inadequate symptom control (such as improvement in OABSS to less than 3) after 3 months of pharmacotherapy. Thus, we concluded that antimuscarinic therapy must be continued even when a poor response is obtained in the first few months of treatment.

The duration of antimuscarinic therapy for OAB varies among different studies [9], and there has been no consensus regarding the optimal treatment duration for OAB patients. In some randomized clinical studies using solifenacin or tolterodine, the treatment intervals were <12 weeks [4-6]. Therefore, the efficacy of these medications may have been underestimated. On the other hand, therapy for more than 12 weeks may be longer than necessary for evaluating efficacy [10,11]. In our opinion, due to the low probability of becoming responsive to therapy after 3 months (Fig. 1), the ideal duration of therapy for evaluating efficacy should be 3 months, unless long-term efficacy needs to be determined [10,11].

We also found that higher OABSSs were associated with improved responsiveness to antimuscarinics, which is consistent with previous studies [1,24]. The coefficient of OABSS was −0.39 (95% CI, −0.61 to −0.18) for the change of OABSS after 12 weeks of antimuscarinic therapy [1]. High scores on the IUSS, a questionnaire similar to OABSS, were also found to be associated with a good therapeutic responsiveness [24]. However, as compared with OABSS, a lower area under the ROC curve was observed with IUSS in this study (0.70 vs. 0.79) [24]. In addition, OABSS had the highest Spearman ρ between the responsiveness and the change of clinical data, as compared with PPBC, IUSS, or IPSS-S (Table 3). Thus, OABSS is a better questionnaire than IUSS for predicting a therapeutic response.

An OABSS≥7 was found to be the optimal cutoff value for predicting responsiveness. Therefore, for patients with baseline OABSS≥7, alternative treatment may be considered earlier if there is no response to antimuscarinic therapy. On the other hand, for patients with a baseline OABSS<7, continuous antimuscarinic therapy may be considered even after 3 months of treatment, especially for patients with a questionable response. As compared with the IUSS cutoff value (4) for predicting response [24], the cutoff values (≥7) for OABSS showed a significant clinical advantage with a larger area under the ROC curve.

Alpha blockers and/or 5-alpha reductase inhibitor can improve storage symptoms in men with benign prostate hyperplasia, and concomitant antimuscarinic therapy may have an additional effect on the improvement of storage symptoms [25]. Despite the presence of benign prostate hyperplasia or concomitant alpha blocker/5-alpha reductase inhibitor, there were no independent predictors to determine responsiveness to therapy in our analysis (Table 2). Our results may exaggerate the therapeutic effect of antimuscarinics, especially in men treated with alpha blockers and/or 5-alpha reductase inhibitor.

However, this study has several limitations. Only 76% of our patients had at least one follow-up visit. D’Souza et al. [26] also reported that only 57.3% of patients obtained a refill of tolterodine ER after the initial prescription. In addition, this study was not a randomized trial, and thus the differences in the therapeutic efficacy of solifenacin and tolterodine may be over- or underestimated.

To conclude, the median interval for the occurrence of a response to antimuscarinic therapy was 3 months, and OABSS was the only independent predictor for a positive response to antimuscarinic therapy. These findings may serve as an important guideline when prescribing antimuscarinic therapy for OAB patients.

Notes

Research Ethics

The study was performed according to the Helsinki Declaration (http://www.wma.net/en/30publications/10policies/b3/) and the study design was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Buddhist Tzu Chi General Hospital (IRB No. 102-05).

Conflict of Interest

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.