Polydeoxyribonucleotide Attenuates Airway Inflammation Through A2AR Signaling Pathway in PM10-Exposed Mice

Article information

Abstract

Purpose

Inhalation of air containing high amounts of particular matter (PM) causes various respiratory disorders including asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and lung cancer. The changes of expression of inflammatory factors by polydeoxyribonucleotide (PDRN) administration in the PM10-exposed trachea inflammation model were evaluated.

Methods

PM10 was administered to mouse trachea to induce acute inflammatory damage, and changes in inflammatory factors were observed after administration of PDRN and 3,7-dimethyl-1-propargylxanthine (DMPX) for 3 days daily. Expression of inflammatory cytokines, adenosine A2A receptor (A2AR), protein kinase A (PKA), 3΄,5΄-cyclic adenosine monophosphate responsive element binding protein (CREB) were detected by enzyme‐linked immunosorbent assay, immunofluorescence, and western blot assay.

Results

PM-exposed trachea showed increased tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α and interleukin (IL)-1β expression, and expression of TNF-α and IL-1β was inhibited by PDRN treatment in PM-exposed mice. PM-exposed trachea showed increased nuclear factor (NF)-κB phosphorylation, and phosphorylation of nuclear factor-kappa B was inhibited by PDRN treatment in PM-exposed mice. PM-exposed trachea showed increased expression of A2AR, but PDRN treatment more enhanced A2AR expression in PM-exposed mice. PKA phosphorylation was not changed and CREP phosphorylation was decreased, however PDRN treatment increased phosphorylation of PKA and CREB in PM-exposed mice. DMPX treatment blocked all the effects of PDRN on PM-exposed mice, demonstrating that the action of PDRN occurs via A2AR.

Conclusions

PDRN treatment attenuated inflammation in the trachea of the PM10-exposed mice. This improving effect of PDRN can be ascribed to the activation of A2AR through the cAMP-PKA pathway.

• HIGHLIGHTS

- Expression of TNF-α and IL-1β and phosphorylation of NF-κB were inhibited by PDRN treatment.

- PDRN treatment more enhanced A2AR expression and increased phosphorylation of PKA and CREB.

- DMPX treatment blocked all the effects of PDRN on PM-exposed mice.

INTRODUCTION

Due to rapid industrialization and urbanization, air pollution in many countries is becoming increasingly severe and causing social problems such as the outbreak of respiratory diseases. Particulate matter (PM) contained in polluted air has been reported to have a detrimental effect on the human body [1]. PM is composed of various components such as polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons and mediates toxic effects. Inhalation of air containing high amounts of PM causes various respiratory diseases such as asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and lung cancer [2-4]. PM 10 (PM10) refers to material with a diameter of <10 μm. The small-sized PMs accumulate in the airways and lungs through breathing and affect the circulatory system [5].

Airways exposed to small-sized PMs secrete proinflammatory cytokines such as inducible nitric oxide (NO) synthase, tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α, interleukin (IL)-1β, reactive oxygen species. Small-sized PMs directly penetrate cell membranes, causing mitochondrial membrane disruption and mitochondrial structure and function changes [6-8]. PMs-stimulated alveolar macrophages decreased cell viability and DNA function [3].

It has been reported that the increase in inflammatory factors can be reduced by adenosine A2A receptor (A2AR) stimulation in lung injury [9,10]. One of the adenosine agonists, polydeoxyribonucleotide (PDRN) is known as a candidate for anti-inflammatory drugs by inhibiting inflammation and apoptosis by selectively stimulating A2AR in lung-injured animals. PDRN is derived from salmon semen and consists of a stable mixture of nucleotides ranging in size from 50 to 1,500 kDa [10,11]. Of the 4 adenosine receptors, PDRN selectively acts on A2AR, and selective stimulation of A2AR effectively inhibits inflammatory substances [10-12].

PDRN administration increases 3΄,5΄-cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) and regulates the pathway leading to phosphorylation of protein kinase A (PKA) and cAMP responsive element binding protein (CREB) [13]. In animal model of lung injury, PDRN treatment can significantly reduce the increase in inflammatory factors through regulation of the nuclear factor (NF)-κB pathway [10]. Treatment of PDRN reduces NF-κB factor phosphorylation and the expression of inflammatory mediators such as NO, TNF-α, and interleukin-6 (IL-6). In animal model of acute lung injury, PDRN treatment can reduce apoptosis by regulating the B-cell lymphoma 2 family through activation of the cAMP pathway [14].

Although various studies have been conducted on the toxic effects of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, a major component of PM, the therapeutic effect of PDRN in PM10-mediated trachea inflammation has not been identified. In this study, the changes in the expression of inflammatory factors by PDRN administration in the PM10-mediated trachea inflammation were evaluated.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals and Treatments

This study was approved by the Institutional Care and Use Committee of Kyung Hee University (KHUASP [SE]-18-126). ICR male mice, 7–8 weeks old (18–20 g), were provided by the Orient Bio (Sungnam, Korea). For the enzyme‐linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) analysis, mice were assigned into the 6 groups (n=7 in each group): sham group, PM10-exposed group, PM10-exposed with 2-mg/kg PDRN treatment group, PM10-exposed with 4-mg/kg PDRN treatment group, PM10-exposed with 8-mg/kg PDRN treatment group, PM10-exposed with 16- mg/kg PDRN treatment group. PDRN was obtained by Kyongbo Pharm. Co. (Seoul, Korea). PM10 was purchased from European Reference Materials (Retieseweg, Geel, Belgium).

For the immunofluorescence and western blot assay, mice were assigned into the 4 groups (n=7 in each group): sham group, PM10-exposed group, PM10-exposed with PDRN treatment group, PM10-exposed with PDRN and 3,7-dimethyl-1-propargylxanthine (DMPX) treatment group. DMPX were purchased from Sigma Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA).

Skin around neck of animals was excised to expose the trachea, and 100 μg/kg (50 μL volume) of PM10 was injected using a 1-mL syringe (30 gauge). One day after injection of PM10, mice were treated with intraperitoneal injection of 8-mg/kg PDRN or 8-mg/kg DMPX for 3 days daily.

Tissue Preparation

Animals were sacrificed 72 hours after intraperitoneal injection of PDRN. Mice were anesthetized with intraperitoneal injection of 10-mg/kg Zoletil 50 (Vibac Laboratories, Carros, France), and tracheas were collected. Trachea tissues were subsequently fixed with 4% buffered paraformaldehyde, dehydrated in ethanol gradually, infiltrated in xylene, and embedded in paraffin. The paraffin blocks were cut into 5-μm-thick coronal slices using a microtome, and the sliced tissues were placed on the gelatin-coated slides.

ELISA Assay

cAMP, TNF-α, and IL-1β concentration was obtained using enzyme immunoassay kit following the manufacturer’s manual, referring to previous paper [15]. cAMP, TNF‐α, and IL‐1β ELISA kits were purchased from Abcam (Cambridge, MA, UK). Standard and diluted samples prepared for cAMP calculation were added to each well. Labeled alkaline phosphatase-conjugate was added to each well. Then, the cAMP complete antibody was reacted for 2 hours. Stop buffer was treated and read at 405-nm wavelength (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). For TNF-α and IL-1β detection, standard and lysed samples were added to each well and incubated for 2 hours. Antibodies for TNF-α and IL-1β were added to each well and reacted for 1 hour. Subsequently, horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-streptavidin buffer was added and incubated for 45 minutes. In the dark, 3,3΄,5,5΄-tetramethylbenzidine development solution was added and incubated for 30 minutes. Stop buff was added to each well and read at 450 nm wavelength (Thermo Fisher Scientific).

Immunofluorescence

Immunofluorescence analysis of tracheal tissues was done, referring to previous paper [10,13]. Trachea tissues on paraffin slides were deparaffinized with xylene, rehydrated with ethanol, deionized water for 5 minutes, and denatured for 10 minutes in boiling 10mM citric acid (pH, 6.0) for 3 minutes at 100°C. Tissue slides were cooled for 30 minutes at room temperature, and blocked with 5% normal goat serum in tris-buffered saline for 1 hour. Tissue slides were reacted with primary antibody against mouse TNF-α or rabbit IL-6 in 1:200 titer overnight at 4°C. The slides were treated with secondary Alexa 488-mosue IgG or Alexa 594-rabbit IgG (1:500 dilution) antibody for 2 hours. The slides were mounted on a coverslip. Fluorescence images were acquired by Leica DMi8 fluorescence microscope (Leica Microsystems, Wetzlar, Germany) wavelength in the excitation/emission to 490/525 nm for Alexa 488 or excitation/emission to 590/617 nm for Alexa 594.

Western Blot Analysis

Western blot analysis of tracheal tissues was done by referring to previous paper [13,16]. Collected trachea tissues were homogenized in cold radioimmunoprecipitation assay buffer (RIPA buffer) with 1mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride. RIPA buffer was purchased from Cell Signaling Technology (Danvers, MA, USA). Homogenized tissues were centrifuged at 14,000 g for 10 minutes at 4°C, and supernatants were collected. Protein 30 μg was separated by 15% sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and subsequently transferred onto polyvinylidene fluoride membranes. After blocking with 5% skim milk overnight, membranes were reacted with primary antibody against mouse β-actin, A2AR, or rabbit phosphorylated PKA (p-PKA), PKA, p-CREB, CREB, p-NF-κB, NF-κB in 1:1,000 titer and then reacted with HRP-conjugated secondary antibody in 1:2,000 titer. Quantitative band intensity was evaluated using Image Pro Plus software (ver. 6; Rockville, MD, USA).

Statistical Analyses

One-way analysis of variance analysis and Duncan posttest were done using IBM SPSS Statistics ver. 23.0 (IBM Co., Armonk, NY, USA). Data were presented as mean±standard error of mean, and statistical significance was defined as P<0.05.

RESULTS

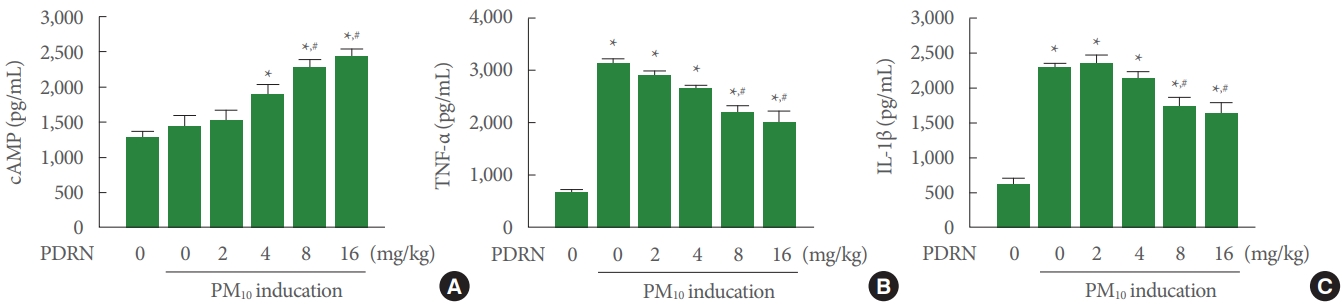

cAMP, TNF-α, and IL-1β Concentration

Fig. 1A shows that cAMP concentration was not changed in the trachea of the PM10-exposed mice. PDRN treatment increased cAMP concentration in the trachea of the PM10-exposed mice. Fig. 1B shows that TNF-α concentration was increased in the trachea of the PM10-exposed mice. PDRN treatment inhibited TNF-α concentration in the trachea of the PM10-exposed mice. Fig. 1C shows that IL-1β concentration was increased in the trachea of the PM10-exposed mice. PDRN treatment inhibited TNF-α concentration in the trachea of the PM10-exposed mice. PDRN had a significant effect at concentrations of 8 mg/kg and 16 mg/kg.

Effect of polydeoxyribonucleotide (PDRN) on cyclic adenosine 3΄,5΄-monophosphate (cAMP), tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α, and interleukin (IL)-1β concentration in trachea exposed to particulate matter 10 (PM10) in mice. Mice were exposed to 100 μg/kg PM10 with treatment of PDRN (2, 4, 8, 16 mg/kg). (A) Concentration of cAMP in PM10-exposed trachea. (B) Concentration of TNF-α in PM10-exposed trachea. (C) Concentration of IL-1β in the PM10-exposed trachea. Results are presented as the mean± standard error of mean. *P<0.05 versus sham group. #P<0.05 versus PM10-exposed group.

TNF-α and IL-1β Expression

TNF-α expression was increased in the trachea of the PM10-exposed mice. PDRN treatment suppressed TNF-α expression, whereas DMPX cotreatment with PDRN abolished inhibitory effect of PDRN in the trachea of the PM10-exposed mice (Fig. 2). IL-1β expression was increased in the trachea of the PM10-exposed mice. PDRN treatment inhibited IL-1β expression, whereas DMPX cotreatment with PDRN abolished inhibitory effect of PDRN in the trachea of the PM10-exposed mice (Fig. 3).

Effect of polydeoxyribonucleotide (PDRN) on tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α, expression in trachea tissue exposed to particulate matter 10 (PM10) in mice. Mice were exposed to 100-μg/kg PM10 with 8-mg/kg PDRN treatment or 8-mg/kg 3,7-dimethyl1-propargylxanthine (DMPX) treatment for 3 days. (A) Sham group. (B) PM10-exposed group. (C) PM10-exposed with PDRN treatment group. (D) PM10-exposed with PDRN and DMPX treatment group. (E) Immunofluorescence intensity of TNF-α. Results are presented as the mean±standard error of mean. *P<0.05 versus sham group. #P<0.05 versus PM10-exposed group. $P<0.05 versus PM10-exposed with PDRN treatment group.

Effect of polydeoxyribonucleotide (PDRN) on interleukin (IL)-1β expression in trachea tissue exposed to particulate matter 10 (PM10) in mice. Mice were exposed to 100-μg/kg PM10 with 8-mg/kg PDRN treatment or 8-mg/kg 3,7-dimethyl-1-propargylxanthine (DMPX) treatment for 3 days. (A) Sham group. (B) PM10-exposed group. (C) PM10-exposed with PDRN treatment group. (D) PM10-exposed with PDRN and DMPX treatment group. (E) Immunofluorescence intensity of IL-1β. Results are presented as the mean± standard error of mean. *P<0.05 versus sham group. #P<0.05 versus PM10-exposed group. $P<0.05 versus PM10-exposed with PDRN treatment group.

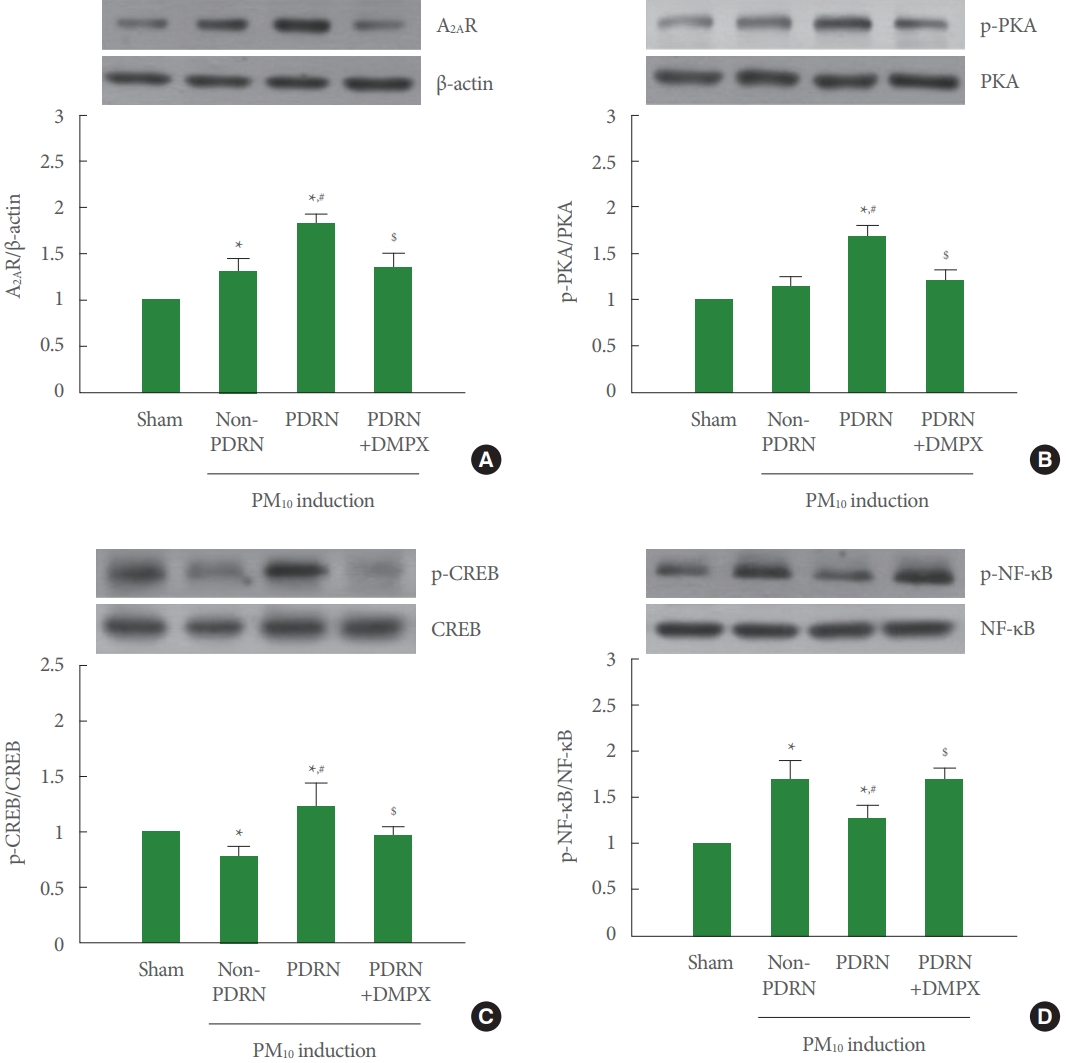

A2AR Expression and Phosphorylation of PKA, CREB, and NF-κB

Fig. 4A shows that A2AR expression was increased in the trachea of the PM10-exposed mice. PDRN treatment more increased A2AR expression, whereas DMPX cotreatment with PDRN abolished increasing effect of PDRN in the trachea of the PM10-exposed mice. Fig. 4B shows that phosphorylation of PKA was not changed in the trachea of the PM10-exposed mice. PDRN treatment increased phosphorylation of PKA, whereas DMPX cotreatment with PDRN abolished phosphorylating effect of PDRN in the trachea of the PM10-exposed mice. Fig. 4C shows that phosphorylation of CREP was decreased in the trachea of the PM10-exposed mice. PDRN treatment increased phosphorylation of CREP, whereas DMPX cotreatment with PDRN abolished phosphorylating effect of PDRN in the trachea of the PM10-exposed mice. Fig. 4D shows that phosphorylation of NF-κB was increased in the trachea of the PM10-exposed mice. PDRN treatment inhibited phosphorylation of NFκB, whereas DMPX cotreatment with PDRN abolished dephosphorylating effect of PDRN in the trachea of the PM10-exposed mice.

Effect of polydeoxyribonucleotide (PDRN) on adenosine A2A receptor (A2AR) expression, phosphorylation of protein kinase A (p-PKA), phosphorylation of cAMP response element binding protein (p-CREB), and phosphorylation of nuclear factor-κB (p-NF-κB) in trachea tissue exposed to particulate matter 10 (PM10) in mice. Mice were exposed to 100-μg/kg PM10 with 8-mg/kg PDRN treatment or 8-mg/kg 3,7-dimethyl-1-propargylxanthine (DMPX) treatment for 3 days. (A) Western blot analysis of A2AR. The top panel is the representative expression of A2AR, and the bottom panel is the level of expression of A2AR. (B) Western blot analysis of PKA. The top panel is the representative expression of PKA, and the bottom panel is the level of expression of PKA. (C) Western blot analysis of CREP. The top panel is the representative expression of CREP, and the bottom panel is the level of expression of CREP. (D) Western blot analysis of NF-κB. The top panel is the representative expression of NF-κB, and the bottom panel is the level of expression of NF-κB. Results are presented as the mean±standard error of mean. *P<0.05 versus sham group. #P<0.05 versus PM10-exposed group. $P<0.05 versus PM10-exposed with PDRN treatment group.

DISCUSSION

It is well known that PM aspiration increases inflammatory factors and accelerates apoptotic cell death [2-4,6]. Reduced cell viability and production of TNF‐α, IL‐1β, and IL‐6 were observed after exposure to PM10 in human bronchial-derived NCI-H358 cells [11]. Since the PM composition in the air has a high content of heavy metals and transition metals, its toxicity may cause damage to the human body [17,18]. The immune system reacts immediately when external harmful substances are introduced to activate the phagocytosis of macrophages, induces neutrophils by activation of chemokines, and damages cells by increasing the secretion of proteolytic enzymes [19-21]. Increased production of TNF-α and IL-1β in the inflammatory response of the airways and lung parenchyma caused acute respiratory distress syndrome or chronic lung diseases [4,10]. In the current study, PM-exposed trachea increased TNF-α and IL-1β expression, and the expression of TNF-α and IL-1β was suppressed by PDRN treatment in PM-exposed mice.

The inflammatory reaction is caused by a number of complex chemical reactions [22,23]. Increased inflammatory factors induced activation of NF-κB through IκB kinase-dependent phosphorylation by degradation of IκBα in lung cells [10]. Activation of NF-κB has been associated with the development of lung inflammation after exposure to various environmental pollutants [24,25]. NF-κB activation was confirmed in human lung biopsy [26] and in vitro cell model exposed to diesel exhaust [27]. PDRN suppressed apoptosis by reducing NF-κB expression through A2AR stimulation [10]. In the current study, PM-exposed trachea showed increased NF-κB phosphorylation, and phosphorylation of NF-κB was inhibited by PDRN treatment in PM-exposed mice.

It may be suggested that A2AR agonists may be useful in the treatment of a variety inflammatory diseases [28]. PDRN is well known as an adenosine A2A agonist and is reported to play an excellent role in anti-inflammatory and cell regeneration [22]. A2AR stimulation by PDRN is well known as a chain reaction of G-proteins that classically induce cAMP cascade responses [12]. It was reported that A2AR tends to initially increase in lung injury of smoke-mediated airway epithelial cells [29]. In the lung injury model, PDRN treatment induced cAMP activation and PKA phosphorylation [10]. In the current study, PM-exposed trachea showed increased expression of A2AR, but PDRN treatment more enhanced A2AR expressed in PM-exposed mice.

Activation of PKA enhanced phosphorylation of CREB, which led to the nuclear localization and activation of CREB [30]. Phosphorylation of CREB exerted anti-inflammatory effect [10,11] and improved short-term memory [31]. In the current study, PM-exposed trachea showed PKA phosphorylation was not changed and CREP phosphorylation was decreased, however PDRN treatment increased phosphorylation of PKA and CREB in PM-exposed mice.

DMPX effectively suppressed the effect of PDRN on lung injury [10,11]. In the current study, The PDRN blocking effect was confirmed through treatment with the antagonist DMPX, and the effect of PDRN was appeared as the result of A2AR stimulation. DMPX treatment blocked all the effects of PDRN on PM-exposed mice, demonstrating that the action of PDRN occurs via A2AR. Our findings suggested that PDRN treatment attenuated inflammation in the trachea of the PM10-exposed mice. This improving effect of PDRN can be attributed to the activation of A2AR through the cAMP-PKA pathway.

Notes

Fund/Grant Support

This study was supported by the Ministry of Education of the Republic of Korea and the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF-2018R1D1A1B07048237).

Research Ethics

This study was approved by the Institutional Care and Use Committee of Kyung Hee University (KHUASP [SE]-18-126).

Conflict of Interest

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTION STATEMENT

- Conceptualization: LH

- Data curation: JJJ, IGK

- Formal analysis: SK, YAC, JSS

- Funding acquisition: BSC

- Methodology: JJJ, IGK

- Project administration: BSC

- Visualization: CWC

- Writing-original draft: LH

- Writing-review & editing: LH